A recent project needed to generate business transaction IDs with the following requirements:

- IDs must be generated in a distributed manner, cannot depend on central node allocation while ensuring global uniqueness.

- IDs must contain timestamps and increase chronologically as much as possible. (Easy to read, improve index efficiency)

- IDs should be well-distributed. (Sharding, required for HBase log storage)

Before reinventing the wheel, first check if there are existing solutions.

Serial#

Traditional practice often implements business transaction IDs through database auto-increment sequences or ID generation services.

MySQL’s Auto Increment, Postgres’s Serial, or writing a small ID generation service with Redis+lua are all convenient and quick solutions. This approach can guarantee global uniqueness, but creates central node dependency: each node needs to access the database once to get a sequence number. This creates availability issues: if we can generate transaction IDs locally and return responses directly, why must we use a network access to get IDs? If the database goes down, nodes also fail. So this is not an ideal solution.

SnowflakeID#

Then there’s Twitter’s SnowflakeID, which is a BIGINT: first bit unused, 41-bit timestamp, 10-bit node ID, 12-bit millisecond sequence number. The bit field lengths for timestamp, worker machine ID, and sequence number can vary based on business requirements.

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|x| 41-bit timestamp |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| timestamp |10-bit machine node| 12-bit serial |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+SnowflakeID can be said to basically meet these four requirements. First, through different timestamps (precise to milliseconds), node IDs (worker machine IDs), and millisecond sequence numbers, it can indeed achieve uniqueness in some sense. A nice feature is that all IDs increase chronologically, so indexing or pulling data is very convenient. Long integer index and storage efficiency is also high, and generation efficiency is excellent.

But I think SnowflakeID has two fatal problems:

- Although ID generation doesn’t require central node allocation, worker machine IDs still need manual allocation or central node coordination, essentially improving rather than solving the problem.

- Cannot solve time rollback issues - once server time is adjusted, duplicate IDs will almost certainly be generated.

UUID (Universally Unique IDentifier)#

Actually, this type of problem already has classic solutions, such as: UUID by RFC 4122. The famous IDFA is a type of UUID.

UUID is a format with 5 versions. I ultimately chose v1 as the final solution. Below is a detailed simple introduction to UUID v1 properties.

- Can be generated locally in distributed manner.

- Guarantees global uniqueness and can handle ID duplication caused by time rollback or network card changes.

- Timestamp (60bit), precise to 0.1 microseconds (1e-7 s). Embedded in ID.

- Within a continuous time segment (2^32/1e7 s ≈ 7min), IDs are monotonically increasing.

- Consecutively generated IDs are uniformly distributed (so convenient for sharding, can be used directly as RowKey in HBase)

- Has existing standards, requires no prior configuration or parameter input, implementations available in all languages, ready to use out of the box.

- Can directly determine approximate business timestamp from UUID literal value.

- PostgreSQL has built-in UUID support (ver>9.0).

Considering all factors, this is indeed the most perfect solution I could find.

UUID Overview#

# Simple way to generate a random UUID in shell

$ python -c 'import uuid;print(uuid.uuid4())'

8d6d1986-5ab8-41eb-8e9f-3ae007836a71We commonly see UUIDs as shown above, typically represented by five groups of hexadecimal numbers separated by '-'. But this string is just the string representation of the UUID, the so-called UUID Literal. Actually UUID is a 128-bit integer. That is, 16 bytes, the width of two long integers.

Because each byte is represented by 2 hex characters, UUIDs can typically be represented as 32 hexadecimal digits, grouped in 8-4-4-4-12 format. Why use this grouping format? Because the original version UUID v1 used this bit field division method. Later UUID versions may have different bit field divisions from this structure but still use this literal representation method. UUID1 is the most classic UUID, so I focus on introducing UUID1.

Below is the bit field division for UUID version 1:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| time_low |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| time_mid | time_hi_and_version |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|clk_seq_hi_res | clk_seq_low | node (0-1) |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| node (2-5) |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

typedef struct {

unsigned32 time_low;

unsigned16 time_mid;

unsigned16 time_hi_and_version;

unsigned8 clock_seq_hi_and_reserved;

unsigned8 clock_seq_low;

byte node[6];

} uuid_t;But bit field division is based on C struct representation convenience. Logically UUID1 includes five parts:

- Timestamp:

time_low(32),time_mid(16),time_high(12), total 60bit. - UUID version:

version(4) - UUID type:

variant(2) - Clock sequence:

clock_seq(14) - Node:

node(48), MAC address in UUID1.

The actual bit fields occupied by these five parts are shown below:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| time_low |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| time_mid | ver | time_high |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|var| clock_seq | node (0-1) |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| node (2-5) |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+In UUID:

versionis fixed to0b0001, i.e., version number fixed to1.Reflected in literal value: the first

hexof the third group in a valid UUID v1 must be1:- 6b54058a-a413-11e6-b501-a0999b048337

Of course, if this value is

2,3,4,5, it represents UUID version2,3,4,5.variantis a field used to distinguish from other types of UUIDs (like GUID), specifying UUID bit field interpretation method. Fixed to0b10here.Reflected in literal value, the first

hexof the fourth group in a valid UUID v1 must be one of8,9,A,B:- 6b54058a-a413-11e6-b501-a0999b048337

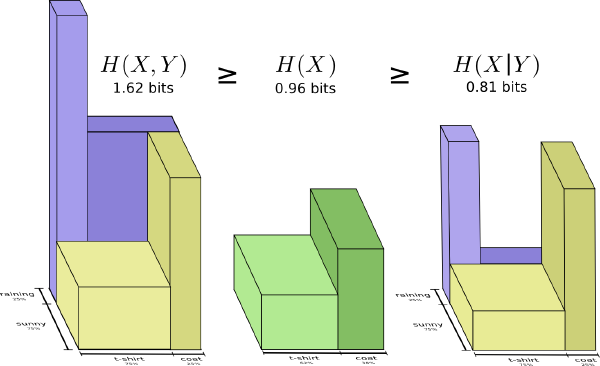

timestampis obtained from system clock, as a 60-bit integer: Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) as a count of 100-nanosecond intervals since 00:00:00.00, 15 October 1582 (the date of Gregorian reform to the Christian calendar).I.e., 100-nanosecond count from 1582/10/15 00:00:00 to now (100 ns= 1e-7 s). This painful design is to create good hashing, maximizing entropy of output ID distribution.

Formula to convert

unix timestampto required timestamp:ts * 10000000 + 122192928000000000time_low = (long long)timestamp [32:64), fill UUID first 32bit with lowest 32bit of timestamp in same ordertime_mid = (long long)timestamp [16:32), fill UUID’stime_midwith middle 16bit of timestamp in same ordertime_high = (long long)timestamp [4:16), generatetime_hiwith highest 12bit of timestamp in same order.However

time_hiandversionshare ashort int, so generation method is:time_hi_and_version = (long long)timestamp[0:16) & 0x0111 | 0x1000clock_seqprevents ID duplication caused by network card changes and time rollback. When system time rolls back or network card status changes,clock_seqautomatically resets, avoiding ID duplication. It’s 14 bits, converting to integer is0~16383. General UUID libraries handle this automatically; for performance, it can also be randomly generated or set to fixed value.nodefield in UUID1 equals machine network card MAC. 48bit exactly matches MAC address length. General UUID libraries automatically obtain this, but because MAC address leakage might have security concerns, some libraries generate based on IP address, or use system fingerprints when MAC unavailable. No need to worry about it.

So actually all UUID v1 fields can be obtained automatically, no human intervention needed. It’s quite convenient.

There are some tips and techniques for reading UUID v1.

UUID’s first group has 32-bit width. Representing time in 100-nanoseconds, that’s (2 ^ 32 / 1e7 s = 429.5 s = 7.1 min). I.e., every 7 minutes, the first group goes through one reset cycle. So for randomly arriving requests, generated ID hash distribution should be very uniform.

UUID’s second group has 16-bit width, that’s 2^48 / 1e7 s = 326 Day, meaning the second group cycles approximately once a year. Can be roughly seen as business date within the year.

Of course, the most reliable method is to directly extract timestamp from UUID v1 programmatically. This is also very convenient.

Some Issues#

A few days ago I needed to merge old business logs. The old system had no concept of transaction IDs, which was painful. Merging new and old logs required generating business transaction IDs for old logs.

UUID v1 generation is very convenient, but manually constructing a UUID to supplement data is painful. I searched Chinese and English internet, StackOverflow for a long time but found no existing python, Node, Go, pl/pgsql libraries or functions to accomplish this. These packages mostly just provide uuid.v1() for external use, never thinking there would be functionality for retrospective ID generation…

So I wrote a pl/pgsql stored procedure that can regenerate UUID1 based on business timestamp and original worker machine’s MAC. Writing this function gave me deeper understanding of UUID implementation details and principles, which was worthwhile.

Stored procedure for generating UUID from timestamp, clock sequence (optional), and MAC, same principle for other languages:

-- Build UUIDv1 via RFC 4122.

-- clock_seq is a random 14bit unsigned int with range [0,16384)

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION form_uuid_v1(ts TIMESTAMPTZ, clock_seq INTEGER, mac MACADDR)

RETURNS UUID AS $$

DECLARE

t BIT(60) := (extract(EPOCH FROM ts) * 10000000 + 122192928000000000) :: BIGINT :: BIT(60);

uuid_hi BIT(64) := substring(t FROM 29 FOR 32) || substring(t FROM 13 FOR 16) || b'0001' ||

substring(t FROM 1 FOR 12);

BEGIN

RETURN lpad(to_hex(uuid_hi :: BIGINT) :: TEXT, 16, '0') ||

(to_hex((b'10' || clock_seq :: BIT(14)) :: BIT(16) :: INTEGER)) :: TEXT ||

replace(mac :: TEXT, ':', '');

END

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

-- Usage: SELECT form_uuid_v1(time, 666, '44:88:99:36:57:32');Stored procedure for extracting timestamp from UUID1:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION uuid_v1_timestamp(_uuid UUID)

RETURNS TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE AS $$

SELECT to_timestamp(

(

('x' || lpad(h, 16, '0')) :: BIT(64) :: BIGINT :: DOUBLE PRECISION -

122192928000000000

) / 10000000

)

FROM (

SELECT substring(u FROM 16 FOR 3) ||

substring(u FROM 10 FOR 4) ||

substring(u FROM 1 FOR 8) AS h

FROM (VALUES (_uuid :: TEXT)) s (u)

) s;

$$ LANGUAGE SQL IMMUTABLE;