The conventional way Go uses SQL and SQL-like databases is through the standard library database/sql. This is a generic abstraction for relational databases that provides a standard, lightweight, row-oriented interface. However, the documentation for the database/sql package only explains what it does, without mentioning how to use it. Quick guides are far more useful than piling up facts. This article explains how to use database/sql and its considerations.

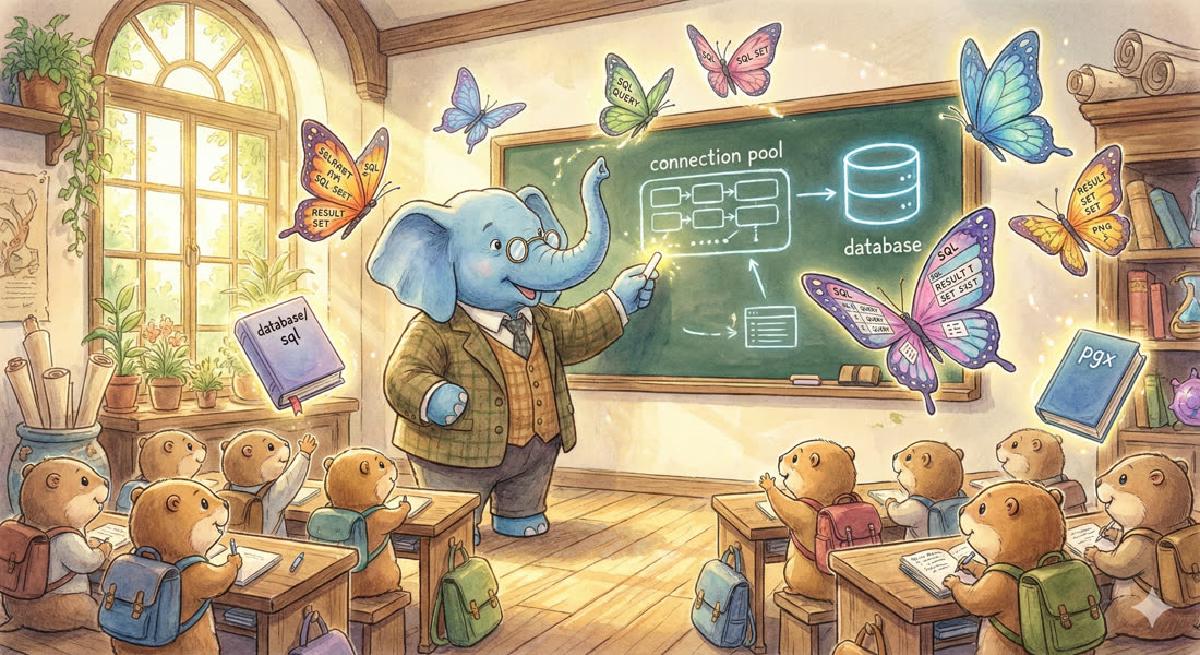

1. High-Level Abstraction#

Accessing databases in Go requires using the sql.DB interface: it can create statements and transactions, execute queries, and retrieve results.

sql.DB is not a database connection, nor does it conceptually map to a specific database or schema. It’s just an abstract interface, with different concrete drivers having different implementations. Generally speaking, sql.DB handles some important and troublesome things, such as operating specific drivers to open/close actual underlying database connections and managing connection pools as needed.

This sql.DB abstraction allows users not to worry about how to manage concurrent access to the underlying database. When a connection is executing a task, it’s marked as in use. After use, it’s returned to the connection pool. However, if users forget to release connections after use, it can produce a large number of connections, very likely leading to resource exhaustion (too many connections established, too many files opened, lack of available network ports).

2. Importing Drivers#

When using databases, besides the database/sql package itself, you also need to import the specific database driver you want to use.

Although sometimes database-specific functionality must be implemented through the driver’s ad-hoc interface, generally when possible, you should try to use only the types defined in database/sql. This reduces coupling between user code and drivers, minimizes code changes when switching drivers, and encourages users to follow Go idioms as much as possible. This article uses PostgreSQL as an example. Famous PostgreSQL drivers include:

Here we use pgx as an example, which has good performance and excellent support for PostgreSQL’s many features and types. It can use ad-hoc APIs and also provides standard database interface implementations: github.com/jackc/pgx/stdlib.

import (

"database/sql"

_ "github.com/jackx/pgx/stdlib"

)Use the _ alias to anonymously import the driver; the driver’s exported names won’t appear in the current scope. When imported, the driver’s initialization function calls sql.Register to register itself in the global variable sql.drivers of the database/sql package, so it can be accessed later through sql.Open.

3. Accessing Data#

After loading the driver package, you need to use sql.Open() to create sql.DB:

func main() {

db, err := sql.Open("pgx","postgres://localhost:5432/postgres")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer db.Close()

}sql.Open has two parameters:

- The first parameter is the driver name, a string type. To avoid confusion, it’s generally the same as the package name, here it’s

pgx. - The second parameter is also a string, its content depends on the specific driver’s syntax. Usually it’s in URL form, such as

postgres://localhost:5432. - In most cases, you should check errors returned by

database/sqloperations. - Generally, programs need to release database connection resources through

sql.DB’sClose()method when exiting. If its lifetime doesn’t exceed the function’s scope, usedefer db.Close()

Executing sql.Open() doesn’t actually establish a connection to the database, nor does it validate driver parameters. The first actual connection is lazily evaluated, delayed until first needed. Users should check if the database is actually available through db.Ping().

if err = db.Ping(); err != nil {

// do something about db error

}The sql.DB object is designed for long connections; don’t frequently Open() and Close() databases. Instead, create one sql.DB instance for each database to be accessed, and keep it until you’re done using it. Pass it as a parameter when needed, or register it as a global object.

If you don’t follow database/sql’s design intent and don’t use sql.DB as a long-term object but frequently open and close it, you may encounter various errors: inability to reuse and share connections, exhausting network resources, intermittent failures due to TCP connections staying in TIME_WAIT state, etc.

4. Retrieving Results#

With a sql.DB instance, you can start executing query statements.

Go categorizes database operations into two types: Query and Exec. The difference is that the former returns results, while the latter doesn’t.

Queryrepresents queries that retrieve query results from the database (a series of rows, possibly empty).Execrepresents executing statements that don’t return rows.

There are also two other common database operation patterns:

QueryRowrepresents queries returning only one row, as a common special case ofQuery.Preparerepresents preparing a statement to be used multiple times for subsequent execution.

4.1 Retrieving Data#

Let’s look at an example of how to query the database and handle results: using the database to calculate the sum of natural numbers from 1 to 10.

func example() {

var sum, n int32

// invoke query

rows, err := db.Query("SELECT generate_series(1,$1)", 10)

// handle query error

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

// defer close result set

defer rows.Close()

// Iter results

for rows.Next() {

if err = rows.Scan(&n); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err) // Handle scan error

}

sum += n // Use result

}

// check iteration error

if rows.Err() != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}The overall workflow is as follows:

- Use

db.Query()to send the query to the database, get the result setRows, and check for errors. - Use

rows.Next()as the loop condition to iteratively read the result set. - Use

rows.Scanto get one row of results from the result set. - Use

rows.Err()to check for errors after exiting iteration. - Use

rows.Close()to close the result set and release the connection.

- Use

Some points that need detailed explanation:

db.Queryreturns result set*Rowsand error. Each driver returns different errors; using error strings to judge error types isn’t wise. A better approach is to doType Assertionon abstract errors, using more specific information provided by the driver to handle errors. Of course, type assertions can also produce errors, which also need handling.if err.(pgx.PgError).Code == "0A000" { // Do something with that type or error }rows.Next()indicates whether there are unread data records, usually used for iterating result sets. Errors during iteration causerows.Next()to returnfalse.rows.Scan()is used to get one row of results during iteration. The database uses wire protocol to transmit data via TCP/UnixSocket. For Pg, each row actually corresponds to aDataRowmessage.Scanaccepts variable addresses, parsesDataRowmessages and fills them into corresponding variables. Because Go is strongly typed, users need to create variables of appropriate types and pass their pointers inrows.Scan. TheScanfunction performs appropriate conversions based on the target variable’s type. For example, if a query returns a single columnstringresult set, users can pass addresses of[]byteorstringtype variables, and Go will fill in the raw binary data or its string form. But if users know this column always stores numeric literals, rather than passing astringaddress and manually usingstrconv.ParseInt()to parse, the recommended approach is to directly pass an integer variable’s address (as shown above), and Go will complete the parsing work for users. If parsing fails,Scanreturns the corresponding error.rows.Err()is used to check for errors after exiting iteration. Normal iteration exit is due to internally generated EOF error, making the nextrows.Next() == false, thus terminating the loop; after iteration ends, check for errors to ensure iteration ended because data reading was complete, not due to other “real” errors. The process of traversing result sets is actually a network IO process that may encounter various errors. Robust programs should consider these possibilities rather than always assuming everything is normal.rows.Close()is used to close the result set. Result sets reference database connections and read results from them. After reading, they must be closed to avoid resource leaks. As long as the result set remains open, the corresponding underlying connection remains busy and cannot be used by other queries.Iteration exit due to errors (including EOF) automatically calls

rows.Close()to close the result set (and release the underlying connection). But if the program unexpectedly exits the loop, such asbreak & returnmidway, the result set won’t be closed, causing resource leaks. Therows.Closemethod is idempotent; repeated calls don’t produce side effects, so it’s recommended to usedefer rows.Close()to close result sets.

This is the standard way to use databases in Go.

4.2 Single Row Queries#

If a query returns at most one row each time, you can use the convenient single-row query instead of the lengthy standard query. For example, the above example can be rewritten as:

var sum int

err := db.QueryRow("SELECT sum(n) FROM (SELECT generate_series(1,$1) as n) a;", 10).Scan(&sum)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

fmt.Println(sum)Unlike Query, if a query error occurs, the error is delayed until Scan() is called for unified return, reducing one error handling check. QueryRow also avoids the trouble of manually operating result sets.

Note that for single-row queries, Go treats no results as an error. The sql package defines a special error constant ErrNoRows; when the result is empty, QueryRow().Scan() returns it.

4.3 Modifying Data#

When to use Exec vs when to use Query is a question. Usually DDL and insert/update/delete use Exec, while queries returning result sets use Query. But this isn’t absolute; it completely depends on whether users want to get return results. For example, in PostgreSQL: INSERT ... RETURNING *; is an insert statement, but it also has a return result set, so Query should be used instead of Exec.

Query and Exec return different results; their signatures are respectively:

func (s *Stmt) Query(args ...interface{}) (*Rows, error)

func (s *Stmt) Exec(args ...interface{}) (Result, error) Exec doesn’t need to return datasets; the returned result is Result. The Result interface allows getting execution result metadata:

type Result interface {

// Used to return auto-increment ID, not all relational databases have this feature.

LastInsertId() (int64, error)

// Returns the number of affected rows.

RowsAffected() (int64, error)

}Exec usage is shown below:

db.Exec(`CREATE TABLE test_users(id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY ,name TEXT);`)

db.Exec(`TRUNCATE test_users;`)

stmt, err := db.Prepare(`INSERT INTO test_users(id,name) VALUES ($1,$2) RETURNING id`)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err.Error())

}

res, err := stmt.Exec(1, "Alice")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

} else {

fmt.Println(res.RowsAffected())

fmt.Println(res.LastInsertId())

}In contrast, Query returns result set object *Rows, whose usage is shown in the previous section. Its special case QueryRow is used as follows:

db.Exec(`CREATE TABLE test_users(id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY ,name TEXT);`)

db.Exec(`TRUNCATE test_users;`)

stmt, err := db.Prepare(`INSERT INTO test_users(id,name) VALUES ($1,$2) RETURNING id`)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err.Error())

}

var returnID int

err = stmt.QueryRow(4, "Alice").Scan(&returnID)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

} else {

fmt.Println(returnID)

}There’s a huge difference between using Exec and Query to execute the same statement. As mentioned above, Query returns result set Rows, and Rows with unread data actually occupy the underlying connection until rows.Close(). Therefore, using Query but not reading return results leads to the underlying connection never being released. database/sql expects users to return connections after use, so this usage pattern quickly leads to resource exhaustion (too many connections). Therefore, statements that should use Exec must never be executed with Query.

4.4 Prepared Queries#

In the two examples in the previous section, instead of directly using the database’s Query and Exec methods, we first executed db.Prepare to get prepared statements. Prepared statements Stmt, like sql.DB, can execute Query, Exec, and other methods.

4.4.1 Advantages of Prepared Statements#

Preparing before querying is idiomatic in Go; query statements used multiple times should be prepared (Prepare). The result of preparing queries is a prepared statement, which can contain placeholders for parameters needed during execution (i.e., bound values). Prepared queries are much better than string concatenation - they can escape parameters and avoid SQL injection. Meanwhile, prepared queries also save parsing and execution plan generation overhead for some databases, benefiting performance.

4.4.2 Placeholders#

PostgreSQL uses $N as placeholders, where N is an integer starting from 1 and incrementing, representing parameter position, convenient for parameter reuse. MySQL uses ? as placeholders, SQLite supports both placeholders, while Oracle uses the :param1 form.

MySQL PostgreSQL Oracle

===== ========== ======

WHERE col = ? WHERE col = $1 WHERE col = :col

VALUES(?, ?, ?) VALUES($1, $2, $3) VALUES(:val1, :val2, :val3)Taking PostgreSQL as an example, in the above example: "SELECT generate_series(1,$1)" uses the $N placeholder form, providing a number of parameters matching the number of placeholders afterward.

4.4.3 Under the Hood#

Prepared statements have various advantages: safe, efficient, convenient. But Go’s implementation may differ slightly from what users expect, especially regarding interaction with other objects inside database/sql.

At the database level, prepared statements Stmt are bound to single database connections. The usual flow is: client sends query statements with placeholders to the server for preparation, server returns a statement ID, and during actual execution, the client only needs to transmit the statement ID and corresponding parameters. Therefore, prepared statements cannot be shared between connections; when using new database connections, they must be prepared again.

database/sql doesn’t directly expose database connections. Users execute Prepare on DB or Tx, not Conn. Therefore database/sql provides some convenient handling, such as automatic retries. These mechanisms are hidden in Driver implementations and won’t be exposed in user code. How it works: when users prepare a statement, it’s prepared on a connection from the connection pool. The Stmt object references the connection it actually uses. When executing Stmt, it tries to use the referenced connection. If that connection is busy or has been closed, it gets a new connection, re-prepares on that connection, then executes.

Because Stmt re-prepares on other connections when the original connection is busy, when accessing databases with high concurrency, many connections are busy, which causes Stmt to continuously get new connections and execute preparations, ultimately leading to resource leaks and even exceeding the server’s statement count limit. So generally, fan-in approaches should be used to reduce database access concurrency.

4.4.4 Query Subtleties#

Database connections are actually interfaces implementing Begin, Close, Prepare methods.

type Conn interface {

Prepare(query string) (Stmt, error)

Close() error

Begin() (Tx, error)

}So there are actually no Exec, Query methods on the connection interface; these methods are defined on Stmt returned by Prepare. For Go, this means db.Query() actually performs three operations: first prepares the query statement, then executes the query statement, finally closes the prepared statement. For databases, this is actually 3 round trips. Crudely designed programs with simple driver implementations might triple the number of interactions between applications and databases. Fortunately, most database drivers have optimizations for this situation. If the driver implements the sql.Queryer interface:

type Queryer interface {

Query(query string, args []Value) (Rows, error)

}Then database/sql won’t use the Prepare-Execute-Close query pattern anymore, but directly uses the driver’s implemented Query method to send queries to the database. For situations where queries are used immediately and security isn’t a concern, direct Query can effectively reduce performance overhead.

5. Using Transactions#

Transactions are a core feature of relational databases. Transactions (Tx) in Go are objects that hold database connections, allowing users to execute the various operations mentioned above on the same connection.

5.1 Basic Transaction Operations#

Start a transaction through db.Begin(). The Begin method returns a transaction object Tx. Calling Commit() or Rollback() methods on the result variable Tx commits or rolls back changes and closes the transaction. Under the hood, Tx gets a connection from the connection pool and maintains exclusive access to it during the transaction. The transaction object Tx’s methods correspond one-to-one with database object sql.DB’s methods, such as Query, Exec, etc. Transaction objects can also prepare queries; prepared statements created by transactions are explicitly bound to the transaction that created them.

5.2 Transaction Considerations#

When using transaction objects, you shouldn’t execute transaction-related SQL statements like BEGIN, COMMIT, etc. This may produce side effects:

- The

Txobject remains open, thus occupying the connection. - Database state no longer stays synchronized with related variable states in Go.

- Early transaction termination causes some query statements that should belong to the transaction to no longer be part of the transaction; these excluded statements may be executed by other database connections rather than the original transaction-specific connection.

When inside a transaction, use methods of the Tx object rather than DB methods. The DB object isn’t part of the transaction; directly calling database object methods executes queries that aren’t part of the transaction and may be executed by other connections.

5.3 Other Use Cases for Tx#

If you need to modify connection state, you also need to use Tx objects, even if users don’t need transactions. For example:

- Creating temporary tables visible only to the connection

- Setting variables, such as

SET @var := somevalue - Modifying connection options, such as character sets, timeout settings.

Methods executed on Tx are guaranteed to execute on the same underlying connection, making connection state modifications effective for subsequent operations. This is the standard way to implement such functionality in Go.

5.4 Prepared Statements in Transactions#

Calling Tx.Prepare creates prepared statements bound to the transaction. When using prepared statements in transactions, there’s a special issue to note: prepared statements must be closed before the transaction ends.

Using defer stmt.Close() in transactions is quite dangerous. When transactions end, they release their held database connections, but unclosed Stmt created by transactions still retain references to transaction connections. Executing stmt.Close() after transaction end, if the originally released connection has been acquired and used by other queries, creates race conditions that may corrupt connection state.

6. Handling Null Values#

Nullable columns are very annoying and easily make code ugly. If possible, they should be avoided during design because:

Every variable in Go has a default zero value. When data’s zero value is meaningless, zero values can represent null values. But in many cases, data’s zero value and null value actually have different semantics. Simple atomic types cannot represent this situation.

The standard library only provides limited four

Nullable types:NullInt64,NullFloat64,NullString,NullBool. There are no types likeNullUint64,NullYourFavoriteType; users need to implement them themselves.Null values have many troublesome aspects. For example, when users think a column won’t have null values and use basic types to receive but encounter null values, the program crashes. Such errors are very rare, hard to catch, detect, handle, or even notice.

6.1 Using Additional Flag Fields#

database\sql provides four basic nullable data types: composite structs using basic types and boolean flags to represent nullable values. For example:

type NullInt64 struct {

Int64 int64

Valid bool // Valid is true if Int64 is not NULL

}Nullable types are used the same way as basic types:

for rows.Next() {

var s sql.NullString

err := rows.Scan(&s)

// check err

if s.Valid {

// use s.String

} else {

// handle NULL case

}

}6.2 Using Pointers#

Java handles nullable types through boxing, wrapping basic types into classes and referencing through pointers. Thus, null value semantics can be represented by null pointers. Go can certainly adopt this approach, though the standard library doesn’t provide this implementation. pgx provides this form of nullable type support.

6.3 Using Zero Values to Represent Null Values#

If data semantically never has zero values, or doesn’t distinguish between zero and null values at all, the most convenient method is using zero values to represent null values. The driver go-pg provides this form of support.

6.4 Custom Processing Logic#

Any type implementing the Scanner interface can be used as the address parameter type passed to Scan. This allows users to customize complex parsing logic and implement richer type support.

type Scanner interface {

// Scan scans a value from database drivers. When conversion cannot be done losslessly, should return error

// src may be int64, float64, bool, []byte, string, time.Time, or nil representing null values.

Scan(src interface{}) error

}6.5 Solving at Database Level#

By adding NOT NULL constraints to columns, you can ensure no results are null. Or use COALESCE in SQL to set default values for NULL.

7. Handling Dynamic Columns#

The Scan() function requires the number of target variables passed to it to exactly match the number of columns in the result set, otherwise it will error.

But there are always situations where users don’t know in advance how many columns the returned results have, such as calling a stored procedure that returns a table.

In such cases, use rows.Columns() to get the column name list. When column types are unknown, use sql.RawBytes as the receiving variable type. Parse the results yourself after getting them.

cols, err := rows.Columns()

if err != nil {

// handle this....

}

// Target columns are dynamically generated arrays

dest := []interface{}{

new(string),

new(uint32),

new(sql.RawBytes),

}

// Pass the array as variadic arguments to Scan.

err = rows.Scan(dest...)

// ...8. Connection-Pool#

The database/sql package implements a generic connection pool that provides a very simple interface with basically no customization options besides limiting connection count and setting lifecycle. But understanding some of its characteristics is helpful.

Connection pools mean: two consecutive queries on the same database may open two connections and execute on their respective connections. This may cause some confusing errors, such as programmers wanting to lock tables for insertion executing two consecutive commands:

LOCK TABLEandINSERT, but ending up blocking. Because during insertion, the connection pool created a new connection, and this connection doesn’t hold the table lock.Connections are created when needed and when there are no available connections in the connection pool.

By default there’s no limit on connection count; you can create as many as you want. But servers often have limited allowed connections.

Use

db.SetMaxIdleConns(N)to limit the number of idle connections in the connection pool, but this doesn’t limit the pool size. Connections recycle quickly; by setting a larger N, you can keep some idle connections in the pool for quick reuse. But keeping connections idle too long may cause other problems, like timeouts. SettingN=0avoids connections being idle too long.Use

db.SetMaxOpenConns(N)to limit the number of open connections in the connection pool.Use

db.SetConnMaxLifetime(d time.Duration)to limit connection lifetime. After timeout, connections are lazily recycled and reused when needed.

9. Subtle Behaviors#

database/sql isn’t complex, but its subtle performance in certain situations can still be surprising.

9.1 Resource Exhaustion#

Careless use of database/sql can dig many traps for yourself. The most common problem is resource exhaustion:

- Opening and closing databases (

sql.DB) may cause resource exhaustion; - Result sets not fully read or failing to call

rows.Close()cause result sets to occupy pool connections indefinitely; - Using

Query()to execute statements that don’t return result sets causes returned unread result sets to occupy pool connections indefinitely; - Not understanding how prepared statements work produces many additional database accesses.

9.2 Uint64#

Go uses int64 internally to represent integers. Be extremely careful when using uint64. Using integers exceeding int64 representation range as parameters produces overflow errors:

// Error: constant 18446744073709551615 overflows int

_, err := db.Exec("INSERT INTO users(id) VALUES", math.MaxUint64) This type of error is very hard to discover; it may seem normal at first, but problems arise after overflow.

9.3 Unexpected Connection State#

Connection state, such as whether it’s in a transaction, which database it’s connected to, set variables, etc., should be handled through Go’s related types rather than SQL statements. Users shouldn’t make any assumptions about which connection their queries execute on; if execution on the same connection is needed, use Tx.

For example, changing connection databases through USE DATABASE is a common operation for many people. Executing this statement only affects the current connection’s state; other connections still access the original database. Without using transaction Tx, subsequent queries aren’t guaranteed to still be executed by the current connection, so these queries may not work as users expect.

Worse, if users change connection state and return it to the connection pool as an idle connection after use, this pollutes other code’s state. Especially directly executing statements like BEGIN or COMMIT in SQL.

9.4 Driver-Specific Syntax#

Although database/sql is a generic abstraction, different databases and drivers still have different syntax and behaviors. Parameter placeholders are one example.

9.5 Batch Operations#

Surprisingly, the standard library doesn’t provide support for batch operations. That is, INSERT INTO xxx VALUES (1),(2),...; - this form of inserting multiple data in one statement. Currently implementing this functionality requires manually constructing SQL.

9.6 Executing Multiple Statements#

database/sql has no explicit support for executing multiple SQL statements in one query; specific behavior depends on driver implementation. So for:

_, err := db.Exec("DELETE FROM tbl1; DELETE FROM tbl2") // Error/unpredictable resultSuch queries are completely up to the driver to decide how to execute; users cannot determine what the driver actually executed or what it returned.

9.7 Multiple Statements in Transactions#

Because transactions guarantee queries executed on them are all executed by the same connection, statements in transactions must be executed one by one in order. For queries returning result sets, result sets must be Close()d before the next query. If users try to execute new queries before previous statement results are fully read, connections lose synchronization. This means statements returning result sets in transactions each occupy a separate network round trip.

10. Others#

This article is mainly based on [[Go database/sql tutorial]]([Go database/sql tutorial]), translated and modified by me with some additions, deletions, and corrections of outdated and incorrect content. Reprints should retain attribution.