Every programmer has used git clone. Hit enter, wait a few seconds, and a complete code repository appears on your disk.

But what about databases?

Want a copy of production data for your test environment? The traditional approach is pg_dump + pg_restore. For a 100GB database, you might finish your coffee and it’s still running. Need parallel testing? Wait another round. Want to give an AI Agent a sandbox to experiment with? Better prepare plenty of disk space and patience.

Recently, a bunch of database companies have been racing to build “Git for Data,” arguing that with data version control, Agents can freely experiment with databases and roll back whenever things break.

But here’s the thing—PostgreSQL has had this capability for a while.

PostgreSQL 18 just takes it to the next level: cloning a 100GB database goes from “minutes” to 200 milliseconds. Not slightly faster—hundreds of times faster. Even more amazing, the cloned database uses zero extra storage. 1TB, 10TB database? Still 200 milliseconds, still zero overhead.

This isn’t magic—it’s Copy-on-Write (CoW) technology finally getting native PostgreSQL support. Let’s talk about this feature and what it means for the entire “data version control” ecosystem.

Copy-on-Write: Why So Fast?#

PostgreSQL 18 introduces a new parameter file_copy_method, with options copy (traditional byte copying) and clone (reflink-based instant cloning). With file_copy_method = clone, run:

CREATE DATABASE db_clone TEMPLATE db STRATEGY FILE_COPY;PostgreSQL calls the operating system’s reflink interface—FICLONE ioctl on Linux, copyfile() on macOS.

Here’s the key: the operating system doesn’t actually copy the data.

It just creates a new set of metadata pointers pointing to the same physical disk blocks. It’s like creating a “shortcut” in your file manager, except this shortcut can be modified independently.

No data movement, just metadata operations. So whether the database is 1GB or 1TB, cloning time is constant—on modern NVMe SSDs, I’ve tested cloning a 120GB database in about 200 milliseconds. A 797GB database takes roughly 569 milliseconds.

Copy-on-Write: Why No Extra Space?#

After cloning, the source and new databases share all physical storage. Only when either side modifies a data page does the filesystem copy that page out for separate storage:

This means: storage overhead = actual changes, not a full copy.

You can run 10 cloned databases for parallel testing simultaneously—as long as they don’t write heavily, storage barely grows. For test environments, this is a huge blessing.

However, not all filesystems support reflink. The good news is most modern Linux distributions have it enabled by default:

| Filesystem | Support Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| XFS | ✅ Full support | Modern mkfs.xfs enables reflink=1 by default |

| Btrfs | ✅ Full support | Native CoW filesystem |

| ZFS | ✅ Supported | OpenZFS 2.2+ requires block_cloning enabled |

| APFS | ✅ Full support | Native to macOS |

| ext4 | ❌ Not supported | Falls back to traditional copy |

If you’re using mainstream distributions like EL 8/9/10, Debian 11/12/13, or Ubuntu 20.04/22.04/24.04, the default XFS already supports and enables reflink.

Still on CentOS 7.9 with ext4? Well, you’re out of luck—time to upgrade.

Key Limitation: No Connections to Template Database#

While this feature is great, there’s one unavoidable limitation: during cloning, the template database cannot have any active connections. The reason is straightforward: PostgreSQL needs to ensure data is in a consistent state during cloning. If connections are running, writes might occur, causing inconsistency.

This limitation has always existed. Previously it was a dealbreaker—you couldn’t take production offline for several minutes waiting for a copy to complete. But now that cloning takes sub-second constant time, this limitation is far less painful. A few hundred milliseconds of brief interruption is acceptable for many scenarios, especially databases used by AI Agents—they’re not that finicky. This opens up many new possibilities.

In practice, to actually clone the database, you need to terminate all connections and execute two consecutive SQL statements:

psql <<EOF

SELECT pg_terminate_backend(pid) FROM pg_stat_activity WHERE datname = 'prod';

CREATE DATABASE dev TEMPLATE prod STRATEGY FILE_COPY;

EOFNote: these two statements can’t be executed separately, but can’t be in the same transaction either (CREATE DATABASE can’t run inside a transaction block).

So you need to use psql stdin approach—using psql -c auto-wraps in a transaction, which will fail.

Optimization in Pigsty#

Pigsty 4.0 adds support for this PG18 cloning mechanism:

pg-meta:

hosts:

10.10.10.10: { pg_seq: 1, pg_role: primary }

vars:

pg_cluster: pg-meta

pg_version: 18

pg_databases:

- { name: meta } # <----- database to clone

- { name: meta_dev ,template: meta , strategy: FILE_COPY}For example, if you already have a meta database and want to create a meta_dev clone for testing,

just add a record to pg_databases, specifying template and strategy: FILE_COPY.

Then run: bin/pgsql-db pg-meta meta_dev, and Pigsty handles all the details automatically.

Of course, there are quite a few details involved—for instance, you need to ensure file_copy_method is correctly set to clone for this feature, which Pigsty has already configured for all PG18+ clusters.

What if the database you want to clone is the management database postgres itself (connections not allowed during cloning)? Or what about terminating all connections before cloning? All handled automatically.

Are There Other Approaches?#

Of course, even 200ms of unavailability is sometimes unacceptable for strict production environments. And if your PG version isn’t the latest 18, you can’t use this feature.

Pigsty provides two more powerful cloning methods for slightly different scenarios:

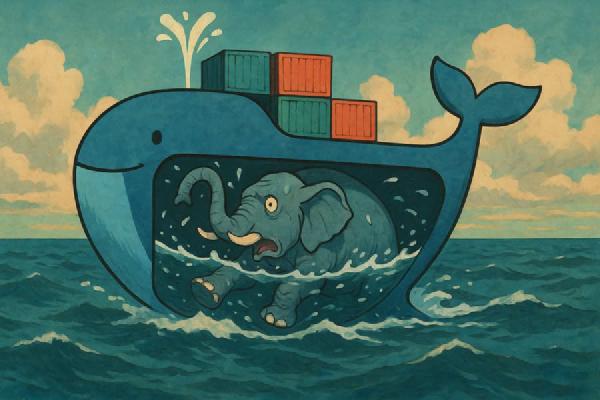

Instance-Level Cloning: pg-fork#

Instance-level cloning uses a similar approach to PG18’s CoW—it requires your filesystem to support reflink (XFS/Btrfs/ZFS). I’ve always strongly recommended XFS for production filesystems, and it’s now the default in many places—this requirement isn’t hard to meet.

With XFS, you can use cp --reflink=auto to clone the entire PGDATA directory, creating a completely independent PostgreSQL instance.

This process is also instant, regardless of database size, and the clone doesn’t consume actual storage until you start writing data, which triggers CoW.

postgres@vonng-aimax:/pg$ du -sh data

797G data

postgres@vonng-aimax:/pg$ time cp -r data data2

real 0m0.586s

user 0m0.014s

sys 0m0.569sOf course, the actual details are more complex—if you just copy like this, you’ll likely get an inconsistent dirty instance that won’t start. So you need to work with PostgreSQL’s atomic backup API to ensure data consistency—the core is this:

psql <<EOF

CHECKPOINT;

SELECT pg_backup_start('pgfork', true);

\! rm -rf /pg/data2 && cp -r --reflink=auto /pg/data /pg/data2

SELECT * FROM pg_backup_stop(false);

EOFIn practice, various edge cases are more complex—for instance, if you want to start the cloned instance, it can’t use the original instance’s port,

can’t dirty the original production instance’s logs/WAL archives, and so on. So Pigsty provides a foolproof pg-fork script to solve this:

pg-fork 1 # Clone instance #1, /pg/data1, listening on port 15432The advantage of instance-level cloning is that you get a completely independent PostgreSQL instance, also using zero extra storage, also completing instantly. But it doesn’t require closing connections to the original template database, so it doesn’t affect production availability. At most, spinning it up consumes some memory, but this is where PG’s double buffering actually has benefits. With the default 25% shared_buffers configuration, you can easily spin up one or two more instances.

Even better, instances cloned this way can use the pg-pitr script to perform Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR) using pgBackRest-based backups.

And this PITR is also incremental, so it’s fast too.

The most direct use case for this mechanism is accidental data deletion—but not enough to warrant a full database rollback.

In such cases, you can use pg-fork to instantly clone an exact replica of the production database,

then do an incremental rollback with pg-pitr to a few minutes earlier, start it up, query the deleted data, and write it back.

Cluster-Level Cloning#

There’s also cluster-level cloning using similar technology—by using a centralized backup repository, you can restore from any cluster’s backup to any point within the retention period.

./pgsql-pitr.yml -l pg-test -e '{"pg_pitr": { "cluster": "pg-meta" }}'This type of cluster cloning doesn’t consume any resources from the original production cluster. Cloud providers’ various “PITR” features are exactly this—spinning up a new cluster and restoring to a specified point in time. But this approach is much slower since data must be pulled from the backup repository and restored to the new cluster—time scales with data volume.

Use Cases#

Three cloning methods, each for different scenarios:

| Method | Speed | Downtime Required | Access Required | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database Clone | ~200ms, constant | Template DB disconnect | Database connection only | AI Agent, CI/CD, rapid testing |

| Instance Clone | ~200ms, constant | None | Filesystem access | Accidental recovery, branch testing, CI/CD |

| Cluster Clone | Minutes to hours | None | Backup repository access | Cross-datacenter recovery, DR drills |

Although pg-fork already provides instance-level “instant cloning” without the few-hundred-millisecond downtime limitation of database template cloning,

this operation requires filesystem access on the database server. And cloned instances can only run on the same machine—not on replicas.

Database cloning has a unique advantage: the operation is “completed entirely within a database client connection,” meaning it can be done via pure SQL without server access. This means you can execute this cloning operation from anywhere that can connect to the database—the only cost is about 200ms of disconnection.

This opens a new door:

AI Agent Scenarios: Give an Agent only database connection privileges. Whenever it needs to “experiment,” let it clone a sandbox for itself. Mess it up? Just DROP it—zero cost. 10 Agents running in parallel, storage overhead nearly zero.

CI/CD Scenarios: Database deployments used to be nerve-wracking. Now you can cheaply clone a bunch of test databases for integration testing, validate DDL migrations on real data before going to production—much more confidence.

Development Environments: Every developer gets a complete database copy with data identical to production, storage cost approaching zero. Break something? Clone a new one—200 milliseconds.

Conclusion#

“Git for Data” has been hyped for years, with various startups raising plenty of funding. But PostgreSQL delivers its own answer in a simple, direct way: No extra middleware needed, no complex architecture, leveraging existing modern filesystem capabilities, with native database kernel support.

A few hundred milliseconds, no extra storage, one SQL statement.

Sometimes the best solution is the simplest one.