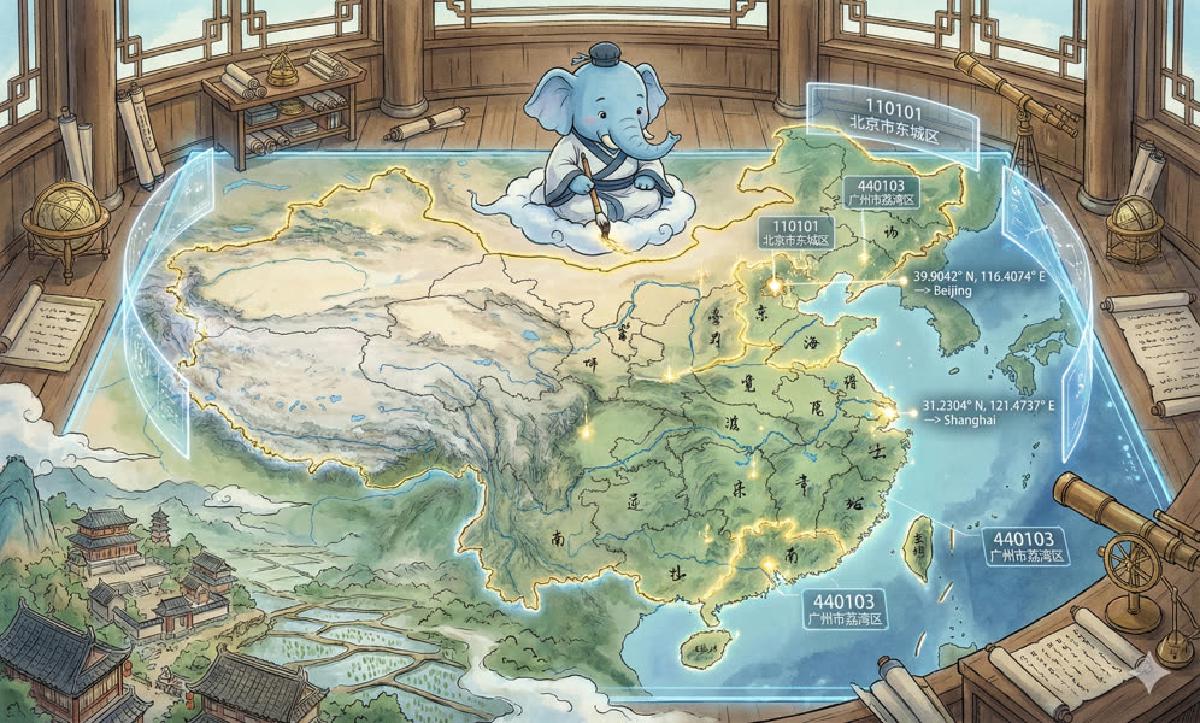

In application development, we often need to solve this problem: determining administrative regions based on user coordinates.

We collect coordinates like 28°00'00"N 100°00'00.000"E, but what we actually care about is the administrative division this point belongs to: (People’s Republic of China, Yunnan Province, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Shangri-La City). This operation of mapping geographic coordinates to a record is called geocoding. Efficiently implementing geocoding is an interesting problem.

This article introduces the solution and optimization approaches for this problem: ensuring correctness while using just a few megabytes of space and completing geocoding in 110μs.

0x01 Correctness First#

Correctness is paramount. We don’t want users to be located in place A but classified as being in place B. However, an embarrassing reality is that many geocoding service implementations are crude beyond belief - the Voronoi method is a typical example.

If we have a series of coordinate points, the perpendicular bisectors of lines connecting these points create a Voronoi partition of the entire coordinate plane. Each cell has a center point as its nucleus, and any point within the cell is closest to that nucleus (compared to other nuclei).

When we don’t have administrative boundary data but have administrative center point data, this is a method that can work reasonably well. Find the nearest administrative center to the user, then assume the user is located in that administrative region. This functionality is very simple to implement.

However, this method handles boundary cases poorly:

Nearest Neighbor Search—Voronoi Method

Reality is always far from ideal. Perhaps for domestic use, this type of error might not have much impact. But when it comes to international sovereign boundaries, this crude implementation could bring unnecessary trouble:

There’s another approach, similar to the “lookup table” method in programming - pre-computing all longitude-latitude to administrative region mappings, and just looking up coordinates when needed. Of course, both longitude and latitude are continuous scalars, so precision is necessarily limited in theory.

GeoHash is such a solution: it cross-encodes longitude and latitude into a single string. The longer the string, the higher the precision. Each string corresponds to a “rectangle” bounded by longitude and latitude. As long as precision is sufficient, this is theoretically feasible. Of course, this solution can’t achieve true correctness and the storage overhead is extremely wasteful. The advantage is that implementation is simple - just having data and a KV service can easily handle it.

In comparison, solutions based on geographic boundary polygons can complete geocoding functionality within a millisecond while ensuring absolute correctness, and may only require a few megabytes of space. The only difficulty might be in obtaining the data.

0x02 Data is King#

Geocoding belongs to typical data-intensive applications, where data quality directly determines the final service effectiveness. To truly provide good service, high-quality data is essential. Fortunately, administrative division and geographic boundary data isn’t classified information - some places provide public access methods:

Both the Ministry of Civil Affairs information query platform and Amap provide geographic boundary data accurate to county level:

Amap Administrative Region Query API

Amap’s data is updated more frequently, has a simple format, and higher boundary precision (more points), but it’s not authoritative and has many errors and omissions.

Ministry of Civil Affairs National Administrative Division Information Query Platform

The Ministry of Civil Affairs platform data is relatively more authoritative, uses topological encoding, strictly avoids boundary overlap problems, and uses unbiased WGS84 coordinates, but has lower boundary precision (fewer points).

In addition to geofence data, another important piece of data is administrative division code data. The 12-digit urban-rural statistical administrative division coding system used by the National Bureau of Statistics is quite scientific, with hierarchical containment relationships, especially suitable as unique identifiers for administrative divisions. But the problem is it’s somewhat outdated - the latest version was released in August 2016, and an updated version might be released after July 2018.

The author has compiled a dataset connecting National Bureau of Statistics administrative divisions with Amap boundary data: https://github.com/Vonng/adcode

Ministry of Civil Affairs data can be obtained directly by opening browser developer tools on that website and extracting from interface response data.

0x03 First Attempt#

Assume we already have a table for national administrative divisions and geographic fences: adcode_fences

create table adcode_fences

(

code bigint,

parent bigint,

name varchar(64),

level varchar(16),

rank integer,

adcode integer,

post_code varchar(8),

area_code varchar(4),

ur_code varchar(4),

municipality boolean,

virtual boolean,

dummy boolean,

longitude double precision,

latitude double precision,

center geometry,

province varchar(64),

city varchar(64),

county varchar(64),

town varchar(64),

village varchar(64),

fence geometry

);

Indexing#

To efficiently execute spatial queries, we first need to create a GIST index on the fence column representing geographic boundaries.

China’s county-level administrative division records aren’t many (about 3000 records), but using an index can still bring dozens of times performance improvement. Since this optimization is too basic and trivial, I won’t discuss it separately. (From over 100 milliseconds to a few milliseconds)

CREATE INDEX ON adcode_fences USING GIST(fence);Querying#

PostGIS provides ST_Contains and ST_Within functions to determine containment relationships between polygons and points. For example, the following SQL will find all administrative divisions in the table that contain the point (116,40):

SELECT

code,

name

FROM adcode_fences

WHERE ST_Contains(fence, ST_Point(116, 40))

ORDER BY rank;The result is:

100000000000 People's Republic of China

110000000000 Beijing

110100000000 Municipal Districts

110109000000 Mentougou DistrictFor another example, the coordinate point (100,28):

SELECT json_object_agg(level,name)

FROM adcode_fences WHERE ST_Contains(fence, ST_Point(100, 28));{

"country": "People's Republic of China",

"city": "Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture",

"county": "Shangri-La City",

"province": "Yunnan Province"

}Quite incredible - with data in place, leveraging PostgreSQL and PostGIS, the code required to implement this functionality is surprisingly little: one line of SQL.

On my laptop, this query takes 6 milliseconds to execute. An average query time of 6ms translates to approximately 6400 QPS on a 48-core machine. This is basically how we did it in our previous production environment code, but because we also had data from other countries and the single-core frequency wasn’t as high as my machine, the average execution time for one query might be around 12 milliseconds.

6 milliseconds seems quite fast already, but it still doesn’t meet our production environment performance requirements (1 millisecond). For real-world production business, performance is important - 10x performance improvement means saving 10x the machines. Can we do better? Actually, simple optimizations can achieve 100x performance improvement.

0x04 Performance Optimization#

Optimizing for Data Characteristics#

An important reason for the slow query above is unnecessary intersection checks. Administrative divisions have hierarchical relationships - if a user is located in a county-level administrative division, they must be in the province-level division where that county is located. Therefore, knowing the lowest-level administrative division naturally determines the higher-level division affiliations; intersection checks with provincial and national boundaries are unnecessary. This might be the most effective optimization - intersection checks between China’s geographic boundaries and points alone might take several milliseconds.

Region Segmentation#

The R-tree index principle can inspire optimization. R-trees are based on AABB (Axis Aligned Bounding Box) indexing. Therefore, the more full and convex the polygon, the better the index performance. For administrative divisions with distant enclaves, performance might deteriorate significantly. Therefore, splitting regions into uniform, full blocks can effectively improve query performance.

The most basic optimization is splitting all ST_MultiPolygon into ST_Polygon pointing to the same administrative division. Further, you can split irregularly shaped administrative divisions into well-formed blocks (typical examples like Gansu Province). Of course, the cost is changing the relationship between administrative divisions and geographic fences from one-to-one to one-to-many, requiring a separate table.

In practice, if you already have county-level administrative division data, usually just splitting MultiPolygons with enclaves into individual Polygons already provides good performance. County-level administrative division boundaries are usually well-formed, so further splitting has limited effect.

Precision#

Correctness is paramount, but sometimes we’d rather sacrifice some accuracy for significant performance improvements. For example, comparing Amap and Ministry of Civil Affairs data, the Ministry’s is obviously much coarser, but for the rough-and-fast internet scenario, low-precision data might actually be more suitable.

| Amap | Ministry of Civil Affairs |

|---|---|

|  |

Amap’s national administrative division data is about 100M, while Ministry of Civil Affairs data is about 10M (4M when represented as raw topological data). But in actual use, the difference in effectiveness is minimal, so I recommend using Ministry of Civil Affairs data.

Primary Key Design#

Administrative divisions have inherent hierarchical relationships - countries contain provinces, provinces contain cities, cities contain districts/counties, districts/counties contain townships, townships contain villages/streets. China’s administrative division codes well reflect these hierarchical relationships. The twelve-digit urban-rural division code contains rich information:

- Digits 1-2: provincial code

- Digits 3-4: prefecture code

- Digits 5-6: county code

- Digits 7-9: township code

- Digits 10-12: village code

Therefore, this 12-digit administrative division code is very suitable as the primary key for administrative division tables. Additionally, when international support is needed, this division code system can be extended by adding country codes at the front (correspondingly, Chinese administrative divisions become the special case where the high-order country code is 0).

On the other hand, when the geographic fence table changes from one-to-one to many-to-one with the administrative division table, the geographic fence table is no longer suitable for using administrative division codes as primary keys. An auto-increment column might be a more suitable choice.

Normalization vs Denormalization#

An important trade-off in data model design is normalization vs denormalization. Separating the geographic fence table from the administrative division table is normalization, while denormalization can also be used for optimization: since administrative divisions have hierarchical relationships, preserving all ancestor administrative division information (or just codes and names) in child administrative divisions is a reasonable denormalization operation. This way, all hierarchical information can be retrieved through one query using the division code primary key.

Historical Support#

Sometimes we want to trace back to a specific historical moment to query the administrative division status at that time.

For example, administrative division changes don’t affect existing citizens’ ID card numbers within that division, only affecting newly born citizens’ ID numbers. Therefore, sometimes using the first 6 digits of a citizen’s ID card to query current administrative division tables might return nothing - you need to trace back to the historical time when that citizen was born to get correct results. You can refer to PostgreSQL MVCC implementation by adding a pair of PostgreSQL’s tstzrange type fields to the administrative division table, marking the valid time period for administrative division record versions, and specifying time points as filtering conditions when querying. PostgreSQL can support building joint GIST indexes on range types and spatial types, providing efficient query support.

However, acquiring time-series data is very difficult, and this requirement isn’t common. So I won’t expand on it here.

0x05 Design Implementation#

Since we’ve already separated geocoding functionality from the division code table, this solution isn’t too concerned with the structure in adcode. We just need to know that with the code field, we can quickly retrieve what we’re interested in from that table, such as a series of administrative division hierarchies, population, area, level, administrative centers, etc.

create table adcode

(

code bigint PRIMARY KEY ,

parent bigint references adcode(code),

name text,

rank integer,

path text[],

…… <other attrs>

);In comparison, the fences table is what we need to focus on, as it’s the critical path for performance loss.

CREATE TABLE fences (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

fence geometry(POLYGON),

code BIGINT

);

CREATE INDEX ON fences USING GiST(fence);

CREATE INDEX ON fences USING Btree(code);

CLUSTER TABLE fences USING fences_fence_idx;Not using administrative division code code as the primary key gives us more flexibility and optimization space. Whenever we need to correct geocoding logic, we only need to modify data in fences. You can even add redundant fields and conditional indexes, putting different sources of data, different levels of administrative divisions, and overlapping geographic fences in the same table, flexibly executing custom encoding logic.

As an aside: if you can ensure your data won’t overlap, you can consider using PostgreSQL’s Exclude constraint to ensure data integrity:

CREATE TABLE fences (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

fence geometry(POLYGON),

code BIGINT,

EXCLUDE USING gist(fence WITH &&)

-- no need to create gist index for fence anymore

);Performance Testing#

How does performance look after optimization? Let’s randomly generate some coordinate points to test performance.

\set x random(75,125)

\set y random(20,50)

SELECT code FROM fences2 WHERE ST_Contains(fence,ST_Point(:x,:y));On my machine, one query now takes only 0.1ms, achieving 9k TPS single-process, which translates to about 350k TPS on a 48-core machine.

$ pgbench adcode -T 5 -f run.sql

number of clients: 1

number of threads: 1

duration: 5 s

number of transactions actually processed: 45710

latency average = 0.109 ms

tps = 9135.632484 (including connections establishing)

tps = 9143.947723 (excluding connections establishing)Of course, after getting the code, you still need to query the administrative division table once, but the overhead of one index scan is very small.

Overall, compared to the pre-optimization implementation, performance improved 60x. In production environments, this might mean saving hundreds of thousands in costs.