What happens when you divide by 0 in a computer? Errors are errors, exceptions are exceptions. The distinction here is quite subtle.

Yes, no typo - the title uses /0 not 0.

So the question arises: What happens when you divide by 0?

Constraints are necessary: In the CS field, on *nix | win operating systems, in any programming language, for integer division operations where the divisor is zero.

The answer isn’t fixed - it can differ across different operating systems, programming languages, and even different compilers.

Division by Zero Exception#

For example, on OS X using C language with Clang compilation, triggering division by zero doesn’t throw an error but returns a garbage value.

$ echo 'void main(){printf("%d",1/0);}' > a.c && gcc a.c 2> /dev/null && ./a.out

1512003000The same code on Linux using C language with GCC compilation triggers a Floating point exception.

$ echo 'void main(){printf("%d",1/0);}' > a.c && gcc a.c 2> /dev/null && ./a.out

Floating point exceptionC++ behaves consistently with C in both environments. As for Windows, I don’t have a Windows machine at hand and VS only supports C++, but if I remember correctly, /Od on Windows throws exceptions through SEH, while /O2 returns garbage values. But who cares about Windows here…

In contrast, Python and Java behave consistently across different systems:

$ python -c 'print(1/0)'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero$ echo "class DZ{public static void main(String[] args){System.out.println(2/0);}}" > DZ.java && javac DZ.java && java DZ

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArithmeticException: / by zero

at DZ.main(DZ.java:1)JavaScript, that oddball with only floating-point numbers, ‘cleverly’ sidesteps this problem with Inf. Won’t discuss this. Note: floating-point division by zero is legal.

Hardware-Level Exceptions#

So what exactly happens during division by zero? Consulting the Intel chip manual, we find that on x86 machines, when DIV or IDIV instructions have a divisor of zero, they trigger interrupt 0, numbered #DE (Divide Error), the so-called division by zero exception.

If you’ve done the small experiment in Wang Shuang’s “Assembly Language”: writing a zero interrupt handler, you’d know how exceptions were handled in the prehistoric era of hardware machine code and assembly programming: programmers had to write their own code as hardware interrupt handlers.

Of course, in environments without operating systems, so-called “exceptions” are actually hardware-level exceptions, just those few types over and over: division by zero, overflow, bounds checking, illegal instructions, etc. Although exception types weren’t many, finding the cause of exceptions or writing appropriate handling functions was indeed quite frustrating work.

Many concepts we’re familiar with, like processes and files, were introduced with the invention of operating systems.

In modern operating systems with file concepts, data is stored in files with independent addressing spaces starting from zero. Programmers only need file paths to access this data; if files don’t exist, they can determine the specific error cause through open’s return value -1 and global errno. Think how blissful this is! In prehistoric times, the entire computer had only one or two addressing spaces corresponding to memory or hard disk, with data at fixed offsets, no so-called files (actually maintaining some metadata at fixed offsets is what we call a file system). If meaningful data couldn’t be read, you could only report an error and crash - there was no such thing as “FileNotExistException”.

Besides files, processes are the same. In worlds without operating systems, even the concept of stacks didn’t exist. Control flow manipulation could be called arbitrary - as long as you didn’t go out of bounds or jump to non-code segments, the whole world was truly vast with freedom to jump anywhere.

In prehistoric times, exception handling meant handling hardware exceptions. Hardware exception types could be counted on one hand - don’t divide by zero, don’t go out of bounds, don’t do stupid things, and you were almost completely unrestricted. Of course, this wasn’t necessarily good - people often claim to yearn for freedom, but faced with true freedom, very few can grasp direction while others only feel anxiety and confusion in the face of infinite choices.

Programmers called for new order, and thus operating systems emerged.

Operating System-Level Exceptions#

Times developed, C language and operating systems appeared, and programmers moved from prehistoric to ancient times. Finally saying goodbye to the bitter days of directly dealing with hardware exceptions. But from C language’s error handling methods, we can still see shadows of that era.

Operating systems introduced many novel abstractions, bringing various novel exceptions: file opening failures, process fork failures. These exceptions, different from hardware-level exceptions, belong to operating system exceptions. Many system calls in the POSIX standard use returning -1 to inform callers of exceptions, passing specific exception reasons by setting global errno. So we often see code like:

if (somecall() == -1) {

printf("somecall() failed\n");

if (errno == ...) { ... }

}But another problem remained: what about original hardware exceptions?

Like the beloved wild pointer out-of-bounds: Segmentation fault:

$ echo 'void main(){int* p;printf("%d",*p);}' > a.c && gcc a.c 2> /dev/null && ./a.out

Segmentation faultAlthough printf isn’t a system call, just a library function, when hardware exceptions occur, library functions don’t return -1 like normal operating system exceptions but directly give programmers a CoreDump Surprise~, Tada~.

Because this type of exception isn’t generated by the operating system, operating systems also scratch their heads facing hardware exceptions. What to do? Obviously, having programmers write their own interrupt 0 handlers is unrealistic. What operating systems can do is wrap receiving these hardware interrupts as operating system interrupts, i.e., the concept of “signals,” then send them to processes. If processes don’t handle these exception signals, the default behavior is to crash.

But in the operating system era, writing handlers for division by zero, out-of-bounds signals often has little meaning… because programmers are often powerless after such exceptions occur. What else can you do - retry for out-of-bounds read/write? Or skip it without reading? For division by zero errors, add a small jitter offset to divide out an astronomical number? Or use garbage values to make do? If you have time to write such handlers, why not add conditional checks before the error statements…

So the best programs can do is handle SIG, log properly, preserve the scene, then honestly crash…

Therefore, at the operating system level (C, C++), we can still clearly see the difference between hardware exception and operating system exception handling methods - the former through signals (Linux), the latter through return values and error codes.

Handling hardware exceptions in C language on Linux:

#include <signal.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void handler(int a) {

printf("SIGNAL: %d",a);

}

int main() {

signal(SIGFPE, handler);

int a = 1/0;

}$ gcc a.c 2> /dev/null && ./a.out

SIGNAL: 8Exceptions in High-Level Languages#

C and C++ are so-called “mid-level” languages. Due to very limited standard library functionality, programmers still need to deal with many ad-hoc details in different operating systems. Java’s emergence can be said to solve (well, at least part of) this problem. We can see that integer division by zero in Java results in java.lang.ArithmeticException, which looks no different from other exceptions. Only its belonging to unchecked RuntimeException seems to hint that this exception is somewhat different from others.

Although JVM provides bytecode interpreters, ultimately JVM still uses C or assembly to map bytecode to system calls and machine instructions. So operating system exceptions and hardware exceptions are still unavoidable. But JVM handles all this for programmers: when hardware-level exceptions like division by zero occur, Java catches SIGFPE, SIGSEGV and other exception signals (on Linux), converting them to internal language exceptions; in contrast, things like file not found system call failures are also wrapped by Java into corresponding exceptions. In Java’s language concepts, at least in handling methods, these exceptions (hardware exceptions, operating system exceptions, application logic exceptions) are not distinguished - programmers can catch and handle them all using the same method if they want.

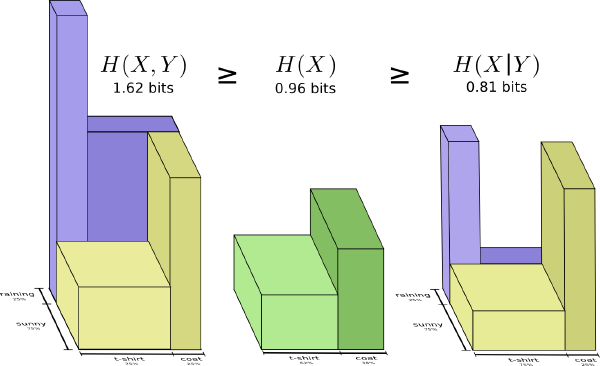

Is the world unified? Although high-level languages like Java formally eliminate distinctions between hardware exceptions, operating system exceptions, and application exceptions, they establish another classification method through semantic design, programming conventions, and engineering practices:

Another Way of Classifying Exceptions#

Let’s first look at the inheritance relationship of Java exceptions and errors. This inheritance tree has three major types of leaf nodes:

Error, RuntimeException, Blahblah...Exception.

BlahblahExceptionare ordinary exceptions defined by programs or libraries that need explicit handling in code.Errorare fatal errors generated during JVM runtime that are not allowed to be handled. Though actually catching throwable is possible…RuntimeException, also calledunchecked Exception, are exceptions that programmers are not recommended to catch.

Actually, we can restore the design intention behind this exception classification, as shown in the table below:

| Cause\Handleable | Programmer can handle (checked) | Programmer cannot handle (unchecked) |

|---|---|---|

| Design flaw | False proposition | RuntimeException |

| Operation failure | Normal Exception, needs explicit handling | Error |

Our old friend division by zero exception changed its disguise: java.lang.ArithmeticException hiding in RuntimeException.

- Design flaws that programmers can handle is itself a contradictory statement.

- Operation failures that programmers can handle are ordinary exceptions in Java. These exceptions are designed to provide a fancy control flow, letting programmers play toss-the-ball games in call chains, making error handling more convenient.

- Design flaws that programmers cannot handle belong to so-called

RuntimeException. This needs explanation: everyone knows preventing NPE is basic programmer cultivation. Unless documentation explicitly states, when getting parameters or return values, the first thing to do is check if they’re null. Similarly, programmers have the obligation to logically ensure division denominators aren’t 0. If programmers don’t do this, it’s a design flaw. Any hardware exceptions or conditions that might lead to hardware exceptions (like: division by zero, array out-of-bounds, wild pointers, stack overflow) should throwRuntimeExceptionat runtime. - Operation failures that programmers cannot handle: On the other hand,

JVMitself is also a program. Humans are mortal, programs crash. Whether due to JVM’s own bugs or environmental conditions not meeting expectations, when JVM falls into serious errors, programmers are helpless about this (fixing JVM yourself doesn’t count!). Such exceptions are so-called operation failures that programmers cannot handle, i.e.,Error.

For exceptions programmers cannot handle, Java treats them as unchecked Exception, meaning no need to explicitly list such exceptions in function signatures. This makes sense - if such exceptions needed specification, then everywhere using pointers and division might throw exceptions, meaning almost every function would need throws RuntimeException in signatures, which is extremely annoying. So uncheck is a necessary property of RuntimeException.

This raises another question - Error is also an unchecked exception. Error is just a special RuntimeException, merely a subdivided subclass of runtime exceptions. Actually from a programmer’s perspective, there are only two types of exceptions: ones I can handle, ones I cannot handle. Whether JVM crashes or there are programmer design flaws, these exceptions are not what programmers can or should handle. Further subdivision is unnecessary, complicating things needlessly. On this point, I think Java’s design is quite disgusting. Also, Java’s RuntimeException is really a garbage bin, throwing all kinds of garbage exceptions in. A more reasonable design should refer to C# Runtime Exception. Runtime only throws a few types of exceptions, all corresponding to hardware exceptions; other exceptions are ordinary exceptions.

Summary#

From the programmer’s perspective, exceptions are divided into two types: handleable application exceptions and unhandleable runtime exceptions

- Application exceptions are error handling methods used by programmers or library authors. Such exceptions are designed to be caught and handled.

- Runtime exceptions belong to system exceptions, with causes including two: hardware exceptions caused by application design flaws, and serious operation failures of JVM or CRT due to environmental conditions. Regardless, such exceptions are designed to make programs crash quickly to avoid greater losses.

From exception causes, exceptions are divided into: design flaws and operation failures

- Design flaws are caused by insufficient consideration by programmers or library authors and should crash immediately to expose errors.

- Operation failures are exceptions caused by unmet environmental conditions. Less serious operation failures can be rescued, like IO Timeout can wait and retry a few times before crashing, or optional steps can be skipped when they fail. Serious operation failures, like JVM itself failing, leave no choice but early death and early rebirth.

Finally, Back to the Original Question#

What happens with division by zero?

On Intel x86_64 Linux:

- CPU executes div instruction, encounters operand 0, generates interrupt 0 (#DE)

- Linux kernel catches interrupt 0, generates SIGFPE (8) for the corresponding process

- Process receives signal

- No handling: generates CoreDump

- Program handles itself: like registering SIGFPE signal handler in C, implementing exception catching

- Runtime suppression: some C runtimes secretly ignore or suppress this exception, happily going home with garbage

- Runtime wrapping and throwing: Java and Python runtimes receive signals and convert them to corresponding internal language exceptions. RuntimeExceptions are generally not caught, so programs generally crash.