Transcription of Data 2025: The year in review with Mike Stonebraker

Data 2025: The Year in Review with Mike Stonebraker & Andy Pavlo#

Recorded on December 10, 2025

A conversation between Mike Stonebraker (MIT CSAIL, Turing Award Winner, Creator of PostgreSQL), Andy Pavlo (Carnegie Mellon University), and the DBOS team.

Introduction#

[0:00] Host (DBOS): Hello everybody. Thank you for joining us today for a look back at 2025, the year in review with Mike Stonebraker and Andy Pavlo.

Our agenda today includes a deep dive into how AI and data management are affecting each other today. Some of the trends—AI trends affecting data management and data management trends affecting AI. Part of that will also touch on how AI is being used to automate database operations.

Then Andy Pavlo will take a look back at some of the industry happenings this year—some of the milestones, acquisitions, new companies, companies no longer with us, companies that are acquired—and talk about how that’s going to shape data management and software development in 2026 and on.

And then we’ll wrap up with a really interesting discussion about how AI is affecting computer science and changing the way it’s taught, the way it’s researched, and how that’s affecting career paths for a lot of people on this event. Then we’ll wrap up with about 10 minutes of Q&A.

For those of you who are familiar with DBOS, you may know that it at one time stood for Database Operating System. The company began as a research project between MIT and Stanford, really prompted by help that co-founder Matei Zaharia asked of Mike to help them with some durable distributed queuing for Databricks. That led to a research project into an operating system built on top of a distributed database as a potential replacement to Linux—something that was much more cloud-native by default.

Today, DBOS stands for Durable Backends that are Observable and Scalable—I had to retrofit that acronym. If you’re familiar with DBOS, it’s an open-source durable workflow orchestration library that really makes your applications, your backends, resilient to failure. It also makes them observable, and through easier queuing makes them easier to scale. As one DBOS user put it really succinctly: DBOS makes it impossible to mess up. It’s one of the reasons why DBOS is so popular with a lot of the new AI application companies where they need their AI workflows to work as intended no matter what situation goes sideways.

Michael will talk a little bit more about the relationship between durability and agentic AI in a moment. But that’s DBOS. So if you’re building software and you want to make it error-proof and observable really easily, check out the DBOS open source libraries.

You may wonder why—if we’re not a database—then why are we hosting a webinar on database R&D? As you know, Mike Stonebraker, the inventor of Postgres, is the co-founder of DBOS. We’re also very good friends with Andy Pavlo at CMU, the inventor of “databaseology” and also the founder of “So You Don’t Have To” AI, which is an AI-powered database tuning service. I encourage you to check that out. And without further ado, let’s jump into the agenda and hear from Andy and Mike.

Part 1: How is AI Impacting Data Management?#

[4:03] Host: Our first topic is: how is AI impacting data management, and how is data management impacting AI? Why don’t we start with you, Mike?

[4:10] Mike Stonebraker: Thanks Andy. And hey other Andy. I just want to mention that I’m pretty sick and not at 100%, so Andy P, you have to go easy on me.

Sam Madden a couple weeks ago characterized Gen AI and large language models as the best thing since sliced bread. He didn’t say it in those terms, but that was effectively what he meant. My point of view is much more muted, and I’d like to just tell you my experience with using large language models.

As I say, I’m interested in enterprise data, and the obvious thing to ask is: well, maybe you can use a large language model to query a data warehouse. There’s been some public benchmarks in this area—BIRD, Spider, and Spider 2—that are reporting reasonably good results in the range of 60 to 90%. That is not my experience with real data warehouses.

We tried using a subset of the MIT data warehouse which has students, classes, faculty, courses, professors—all that sort of stuff in it. We got real users—in fact, CSAIL, the lab I’m in at MIT, is a real user of this MIT data warehouse. We created some real user queries from real users, figured out what the gold SQL was that corresponded to those queries, and so we had pairs of text and gold SQL.

We tried out various LLMs on the MIT data warehouse and we got accuracy of zero. Not low—zero. It couldn’t do anything.

So then we tried all the standard techniques—RAG, decomposing the queries into simpler pieces, adding in data from other sources—and we could nudge the accuracy up to about 20%. If we added in that we gave the LLM the actual table or tables that they had to go look at, it got to like 30%. But nowhere near ready for prime time.

Now you might say, well maybe that stuff is an outlier. We tried this on seven different real data warehouses and we got the same results every time.

Now, some people have reported better results, but I’m pretty skeptical. Here’s why. What are the characteristics of the MIT data warehouse that makes it difficult?

Number one, this is not public data. There’s no way for an LLM to look at this data because it’s behind all kinds of privacy stuff and security stuff. So: not public data.

Number two, MIT is pretty idiosyncratic. If you want to know who majored in computer science in the last two years—that’s not a query the MIT data warehouse can answer because MIT doesn’t use lingo like “computer science.” Computer science is actually Course 6.2, which is what you need to use. There’s also J-term, which is a one-month term in January. None of this you can expect an LLM to know anything about.

The third problem is what I call semantic overlap. The MIT warehouse is full of materialized views, and they’re there to increase performance of popular queries. But the problem is it gives you multiple ways to solve any given query, often with slightly different semantics—like some data is monthly, some data is weekly, and so forth.

And then the fourth thing is complicated queries. These mostly are three and four-way joins with aggregations in them. They’re fairly complicated.

As a result, if your database has any of these four characteristics—not public, idiosyncratic, semantic overlap, and complicated queries—I’m not optimistic that we’re going to get anywhere using an LLM.

[10:00] So my point of view is actually somewhat different. The way to do text-to-SQL well—first of all, the question you want to ask in an enterprise setting is: I have an ERP system, I have a CRM system, I have a whole bunch of other systems, lots of text, and I want to query things like “who is a supplier of stuff to me that’s also a customer?” This requires querying data sources that are all private and a mix of text and SQL. Sort of the data lake problem.

How are you going to solve a data lake problem? Let me give you a simple example. We have a student who’s working with the city of Munich in Germany, dealing with their transportation department. There are all kinds of queries like: why is this green signal not longer at this particular intersection? Or what’s the maximum speed allowed of a tram when it’s going through an intersection that doesn’t have a light on it? And there’s half a dozen different data sources that the city of Munich has that can answer this question in theory. This is a standard data lake.

My point of view is the easiest way to do that is to wrap these data sources into a very small subset of SQL so that a user can tell you what he wants. I’m a fan of having the top level of such a system be SQL-oriented and not LLM-oriented. That’s something I’m working on. This may be an outlier, but it may not be. Maybe Bedrock, the recently released Amazon system, will help in this area.

I should just leave you with: try the following query to your favorite LLM. The query is: “How many MIT professors have a Wikipedia page?” There are two problems with this query. One is the answer to who’s an MIT professor is in the MIT data warehouse—all the stuff I’ve already talked about. And then the second problem is Wikipedia, which is a data source, and there’s a lovely user interface to Wikipedia—you just type in somebody’s name and you get their web page. Now it turns out LLMs have recently started being able to do that. But I can easily give you a more complicated question that they can’t answer.

My point of view is you want to put a wrapper around the MIT data warehouse that makes it simple enough that you can actually answer such a question doing text-to-SQL—or text to a small subset of SQL—and then you simply wrap the Wikipedia data source with a “find Andy Pavlo” or “find whoever you want to find.” And then you want to just do a join between those two systems. You want to do iterative substitution because there are a lot more Wikipedia pages than there are professors at MIT.

This becomes, in my opinion, a query optimization problem that query optimizers are best in addressing. So that’s the direction I’m heading.

As I say, this should be taken with huge grains of salt. Number one, I’m only interested in enterprise data, and other people are interested in lots of other stuff. And I’m only mostly interested in data that is inside a firewall and unavailable to LLMs. So my experience is a little bit muted. In my opinion, LLMs work great on certain things and are probably not the right answer to everything.

With that, Andy Pavlo has a more optimistic view of the world.

Part 2: Andy Pavlo on LLMs and Vibe Coding#

[15:21] Andy Pavlo: I think I would say also the Wikipedia article about me got taken down because I think the bio said I was born in the streets of Baltimore—which is like, I was born in Baltimore, obviously not in the streets.

So yeah, I’m way more optimistic about what LLMs are accomplishing. In the case of natural language to SQL, for certain challenges and certain things, yeah, it’s going to struggle with that. But I’ve been mostly interested in greenfield applications—you know, the future enterprise applications people are going to build have to start somewhere, and they’re starting now.

With Andrej Karpathy coining the term “vibe coding” in the last year, we’re seeing this huge proliferation of people developing new applications that are written almost entirely by LLMs or these coding agents. You say, “Oh well, is that code going to be better or worse than what a human can write?” It’s about the same, right? Because it’s being generated by models trained on the giant corpus of all this code that’s out there. Humans write sometimes good code, sometimes bad code—LLMs are going to do the same thing.

I’m pretty bullish on what LLMs can do, at least as coding agents. Just speaking from experience in our own course that we teach here at Carnegie Mellon—our projects are all in C++. A year ago, the LLMs could maybe solve some of them and not all of them. It would generate code but not all that code was actually correct or useful. It’s getting to the point now for our projects where almost they can be entirely written and solved by LLMs.

So I think the vibe coding stuff is real, and I think we’re going to see way more database-backed applications going forward. Now, the challenge is you have all these agents generating this new application code that are then going to interact and read and write data in a database system. So now we have to handle all that’s coming at the database system.

In the before-LLMs era, you’d have all this application code written by humans, and they would hit up a database system, and you were lucky if a human or DBA was available to actually maintain and optimize and monitor these database systems. So now you have a human not writing the code and now you have no human actually monitoring the database system—and that’s sort of a recipe for potential disaster.

[18:01] On the research side for myself, we’ve been looking at for several years now the use of machine learning and AI technologies to automate the administration and optimization of these database systems. It’s not something that AI all of a sudden enables for us—people have been trying to do this going back to the 1970s. Some of the first work was being done on trying to automatically pick indexes in relational databases. One of the first papers is in SIGMOD in 1976. So people have been doing this for a long time. The Microsoft AutoAdmin project was trying to do this as well.

But what we’ve been working on is the ability to look at the database system holistically—trying to tune everything you could possibly want to tune in a database system to account for the random queries showing up from these vibe-coded applications, and also looking at the lifecycle of the database system.

It turns out the LLMs are pretty good at this. One of the things that we’ve been looking at now is how to tune everything a database system exposes to you all at once. There’s a lot of work on how to tune like “what’s the best indexes you need” or “what’s the best knobs you need for the system”—think of like shared_buffers in Postgres and the InnoDB buffer pool size in MySQL. But all these tools have been targeting one thing. So we’ve been looking at: how can you tune everything all at once? Because that allows you to find the true global maximum configuration for your database.

In our latest work in this space, we’re not using LLMs to make these decisions, but we are using LLMs to allow us to do knowledge transfer between different types of databases or different database deployments. So we can tune in a single algorithm—we can tune indexes and knobs and query plan hints and table level knobs, index logs. Basically everything that Postgres exposes to you. We can tune that all together.

But now you have to build very specific models that are just for this one database instance. And our latest work is leveraging LLMs to identify databases that are sort of similar to each other but not exactly the same. And we can take all the training data we’ve collected from tuning this one database and apply the knowledge to this other database, and it works surprisingly well.

The point I was going to make about the performance of these algorithms is: the current research shows that one of these bespoke customized algorithms that’s dedicated to database optimization and database tuning can do about two to three times better than what an LLM can do. But the LLMs can do this pretty quickly. ChatGPT can spit something out in 15 minutes for your database, whereas our best algorithm can now take 50 minutes. So there’s this trade-off between how fast you want things done versus how good you want things to be. It’s a combination of these two things depending on the severity of the issues and what you need—you may want to choose one versus another.

[21:21] Now the other cool thing we’re looking at with LLMs—and why I’m very bullish on this—is the reasoning agents: the ability to identify issues or problems and then identify what sub-agent or what tool you want to invoke to solve it. So if there’s an anomaly detection, there’s some kind of latency issue in your database system, the reasoning agent can then decide, “Oh, I want to run this tool because that’s going to build my indexes because that’s the problem I think I have right now. I want to run this other tool because I need to optimize my storage capabilities.”

That’s the really cool thing that I think is going to come out in the next year or so: the ability to now start looking at a bunch of different problems simultaneously and deciding which sub-agent to call out to. And the sub-agent could be an LLM, it could be one of these bespoke algorithms. So I think that’s pretty exciting, and I think LLMs are certainly a game changer in this space.

Part 3: Agentic AI and Database Technology#

[22:18] Mike Stonebraker: I think my point of view is that at least in the data management world, autotuning should be successful because it ought to work and it ought to be commercially viable. So I’m enthusiastic that “Son of OtterTune” is alive even if OtterTune didn’t make it.

[22:52] Andy Pavlo: I would say the challenge we faced with OtterTune was—because we weren’t hosting the database system—we had this form factor issue where someone had to give us permissions to connect to the database. With OtterTune also, it was passively tuning, meaning it was on the outside of the system trying to observe what happened and then make changes and then try to observe what happened later on.

The new work we’ve been doing—since we’re not trying to host the database system but we’re looking to integrate with one of these existing platforms that are out there now—is if you put a proxy in front of the application and the database server (think like PgBouncer, PgCat, PgDog—there’s a bunch of these ones for Postgres and other systems now), you can see the queries as they arrive and you can actually start to manipulate them as they come in. We’re still not hosting the database system itself, but at least now we’re seeing the effects of the changes that we make. That has made a big difference in what we’re able to do, whereas OtterTune couldn’t do that.

From a commercial side, the way we’re approaching this now is rather than have a standalone product that someone has to sign up for, connect their database system and give us permissions and so forth, we’re looking to do—we’re in discussions to do—OEM white-label integrations with the existing platforms that are out there. That just allows us to focus on the ML database side of things and less about the developer experience and onboarding process.

[24:20] Mike Stonebraker: Yeah, so anyway, best of luck to you. I hope you succeed.

Andy Pavlo: Thanks Mike.

[24:26] Mike Stonebraker: One thing I would like to talk about is the entire world is in love with agentic AI. Agentic AI means to me that you’ve got a workflow of stuff—some of it is LLM, some of it is AI, and some of it is whatever. Which is: if an LLM can’t do it directly, maybe you can put some stuff around it that will make it more successful. And we’ve been doing that a lot at MIT.

One of the things that DBOS found out early on was that by and large, agentic AI applications wanted durable computing because a lot of this stuff is long-running and if you get an error, you don’t want to redo everything. So durable computing is a big deal in agentic AI. There’s a bunch of commercial products that do it.

But so far, agentic AI is largely what I call read-only—you query a bunch of places, you put together, you know, “well, I predict Andy Pavlo is going to be successful with Son of OtterTune or whatever.”

I think it will take very little time for agentic AI to become read-write. And what that means is that durable computing is basically the D in ACID in transaction systems. It’s exactly the same thing. The way everybody is approaching durability is using database techniques. You have a log, and if something bad happens, you rewind and then play forward.

[26:39] So it is going to be a database issue, and the thing that’s marvelous is that it requires you to put application state into the database. So as Andy Pavlo said earlier, gradually I am pretty sure that the database is going to take over storing state for applications—because that way you get durability.

But the minute you have read-write… My favorite example is: suppose you’re running an online bicycle store. Here is a rough sketch of the server side to such a system. The client comes in and says, “I want to buy an XYZ bicycle.” So your first action is to say, “Well, do I have one?” So you need to query inventory and then reserve it if you have it.

Then secondly, if you have it, then you want to make sure you want to do business with this customer. That can be an LLM to say: does this customer return too much stuff? Does he have a bad credit rating? Etc.

If that’s all okay, then the third thing you do is take his money—and that’s PayPal or whatever your favorite system is. And if that’s okay, then you ship the bicycle.

So it’s basically four steps, each of which is a transaction, and most of them are updates. For example, if you give the fulfillment system a bad address, then it’s got to unwind everything. There are a bunch of updates in these various steps.

So that’s a case where there are updates, and if you just—you’ve got to deal with the failure scenario. Durability just deals with the forward scenario, meaning finish your workflow. You also have to deal with unwinding it, and that requires some notion of atomicity.

[29:04] I think it’s a huge deal to figure out what ACID actually means for workflows. I’m just touting a paper I wrote for CIDR that’s going to appear in January, which I think has an interim solution, but I don’t think is the final solution. So I think figuring this stuff all out is going to take a bit of time.

The other thing is that the way LLMs are currently structured, most of them are non-deterministic. So if you have a bug in your code, chances are you won’t be able to repeat it. Repeat the bug. This is something database people have known about for years and years and years. These are called Heisenbugs—which are unreproducible—as opposed to Bohr bugs, which you can reproduce. Jim Gray wrote a bunch of stuff about this eons and eons ago. We’re clearly going to revisit all of this.

[30:02] So I think this is a case where database technology is going to be wildly helpful in making agentic AI, you know, ACID-plus or whatever it is that’s going to mean. I think that is going to be a huge deal.

And I think the programming language stuff—it is already proven that it’s very helpful. Vibe coding does work. It works best on greenfields—absolutely true. The problem is that 95% of enterprise programmers are not in a greenfield situation. So then you got to deal with what’s there.

And it’s also well known that vibe coding does best if stuff is well-structured. And the trouble is that’s not true in a typical enterprise. The system gets updated, maintained, hacked, updated, maintained, hacked—and eventually it gets so ugly that you throw it away and rewrite it.

So I think we have to change the way enterprises actually write software in order to take maximum advantage of vibe coding. I think there’s lots and lots of work to be done.

Part 4: 2025 Industry Recap - M&A and Market Trends#

[31:43] Andy Pavlo: Well, it’s not just M&A—it was a wild year in databases. I feel like this year there was more activity than maybe the year before.

Maybe we’ll start off with the major acquisitions. Probably the biggest one was Databricks bought Neon, and then soon after Snowflake bought Crunchy. So there’s a lot of activity in the Postgres space—we’ll talk about that in a second.

IBM bought two database companies. They bought DataStax, the main company building out Cassandra, earlier this year. And then I think they announced this week that they bought Confluent, the main company backing Kafka. So those are pretty big plays.

In terms of funding rounds, there was ClickHouse, Supabase—they raised big rounds. Databricks raised another big round because they always do, waiting to go IPO. Informatica got bought by Salesforce. SkyDB got rebought by MariaDB—which is a weird one because they forked it off as a separate company I think last year and then they bought it back this year.

The other big announcement was Fivetran is merging with dbt—so that I think probably will get solidified or finished next year.

So yeah, it was again a lot of activity.

[33:17] In terms of database companies going under, I made a prediction that there’ll be a lot more companies failing in 2025. There’s a Gartner report from about two years ago that sort of surmised the same thing. The only two or three companies I can think of that went under is: Voltron Data announced that they were closing shop a few weeks ago. Fauna closed shop in May. There’s a Chinese MySQL hosting company called MycaleDB that went under earlier this year.

So I was wrong about that. I thought there’d be more database companies closing. A bunch of database friends at database companies have been telling me it’s actually been a really good year. So that’s very positive. I was wrong about more companies failing. Of course, some did, but not as many as I thought there was going to be. And maybe some companies are barely hanging on, but who knows?

There were two companies that went to private equity: Couchbase and SingleStore. SingleStore got bought by a private equity firm called Vector, and they were the ones that bought MarkLogic a few years ago. So they have some experience in running database companies. But usually when private equity buys a company, they kind of get put into maintenance mode. So hopefully Couchbase and SingleStore can get past that.

[34:50] In terms of the overall vibe of the year—I mean, obviously it was another banner year for Postgres. Obviously with Mike—you know, I like how at the beginning he’s listed as the inventor of Postgres and I’m listed as the inventor of like a meme term “databaseology.” Certainly not the same, but I’ll take it. And also we could have put the Turing Award too—that’s more important.

Yeah, there was a wild year for Postgres, right? Databricks bought Neon. They also bought Mooncake, which gives them capability to have Postgres read and write to Iceberg. Microsoft just put out Horizon DB—it’s their hosted version of Postgres that has an architecture similar to Neon with disaggregated storage. They announced that I think two or three weeks ago—something they’ve been working on.

So it’s just more and more Postgres.

[35:42] The only other potential competitor to Postgres—if you would call it that—in the open source database space was MySQL, but that ship has sailed. Plus Oracle fired basically the entire MySQL development team that wasn’t working on HeatWave. They fired all of them back in September. So there really isn’t any major company putting all the energy into building out MySQL. It’s basically Postgres has won the space.

So that’s super exciting. The Postgres codebase—it’s pretty, it’s beautiful. It’s a great front end. The back end is a little dicey, and I’ve written blog articles, we’ve reported this as well.

The effort out of Supabase to integrate OrioleDB is pretty exciting because that’s a modern implementation of multi-version concurrency control and other things that Postgres—I mean, Mike, you did you guys did it in the 80s, there wasn’t really systems to look at to say how to do this. So hopefully they’re going to write the wrongs of what you guys did back in Berkeley back in the 80s.

[36:45] Anyway yeah, so the database commercial space is super energetic now. And like I said, there’s a lot of these vibe coding applications being generated and Postgres is sort of the default choice for a lot of these things.

One more thing also to mention too—there’s two major efforts announced to make distributed Postgres. There’s Multigres out of Supabase, and that’s being led by the guy that invented Vitess at MySQL, which was then commercialized as PlanetScale. And then PlanetScale also announced that they have a project called Naki that’s trying to do a similar sharded, shared-nothing version of Postgres.

What’s really fascinating about this is like this is not the first time people have tried to make distributed versions of Postgres. There was a bunch of work in the late 2000s, early 2010s from companies like Translattice, Greenplum—I think Huawei had a project in this space. But no one’s really successfully done this for OLTP workloads.

And so I think there’s enough energy now where the time is actually right where you actually can finally have a scale-out distributed version of Postgres—either through Multigres or Naki. That’s one major thing that I’m looking forward to next year that I think will come out.

Part 5: The Future of Postgres and Vector Databases#

[38:14] Mike Stonebraker: Well, while we’re on the subject of Postgres, I think Postgres has and will continue to take over the world. The reason is that all the major cloud vendors have bet the ranch on the Postgres user interface. The wire protocol is going to be omnipresent.

They’ve either got to pick something to code to or do their own thing, and every single one of them has picked the Postgres wire protocol.

I think the reason that was a good choice was a whole bunch of years ago Oracle bought MySQL, and that soured the community that this was going to be anything that looked like a community.

The thing I find absolutely amazing about Postgres is that the system is not owned by any enterprise—it’s run by a collection of very, very bright folks who work for a variety of places. So you should think of Postgres as the way open source was supposed to be. It is by the community and for the community.

[39:46] I wanted to actually just talk about a couple other things. Number one, somebody mentioned Kumo in the chat. Yeah, we’ve looked at Kumo. Kumo does predictions. They don’t do text-to-SQL. So they solve a different problem.

The other thing is there are other distributed Postgres-like things. Greenplum is one. Cockroach is another. Yugabyte is another one. There’s a couple more whose names escape me. But I think betting the ranch on Postgres is absolutely the correct thing to do today if you haven’t done it already.

[40:43] The other thing I’d like to point out is that Andy and I wrote a paper a couple years ago called “What Goes Around Comes Around… and Around” or something like that. All of you should go back and read that paper because in my opinion, that is a fabulous predictor of what’s going to happen.

Just for example, there’s a lot of interest in vector indexing or in vector databases. Well, what is a vector database? A vector database is a bunch of blobs—relational style—with a graph-oriented index.

And any of you who’ve read Frank McSherry’s work, he clearly shows that the best way to do graph retrieval is: encode the hell out of the graph, put it into main memory, and write a custom query executor to do that. And the successful vector databases seem to be doing exactly that.

So my point of view is: go read that paper which I think is very prescient as to what’s going to happen.

[42:11] Host: Thanks. We’ll get a link to that—share it with everybody along with the recording of the event.

Quick question on this before we turn to the future of CS. You just mentioned vector databases. There were quite a few questions about the vector database segment. Maybe Andy—are there any vector databases you like more than others? Just your thoughts on the vector database space in general?

[42:36] Andy Pavlo: I gotta be careful with my words because I don’t want to piss people off.

I mean, I like the Weaviate guys. I haven’t used the system, but in terms of understanding what they’re actually doing—because they’re very open, it’s open source, the documentation is well written—I can understand what they’re doing more so maybe than the others. We’ve had all the vector database companies give talks with us that are on YouTube.

The question for these vector database guys that they have to figure out—and this is something that I did talk with the Weaviate CEO a few years ago—was: right now they’re not being used as the databases of record. They’re basically JSON—as Mike said, JSON blobs with these vector embeddings you put inside them and they build the indexes for them. Right now a lot of people are treating them almost like an Elasticsearch, where it’s like the second copy of the database where you can run your nearest neighbor searches and not interfere with the data warehouse or the regular OLTP workload.

[43:48] So they’re going to come to a point where they have to decide whether they want to remain as like an Elasticsearch—where it’s like the database on the side that’s very specialized (which is fine, there’s a market for that)—or they want to start being the database of record. At which point, you have to start adding basically all the things that a Postgres or Cockroach or Oracle would provide you, like transactions, SQL, etc.

So they’ll have to decide how they want to approach that.

Now I will say that the challenge though is: at the end of the day, the vector index is just that—it’s an index. So with systems like Postgres that are highly extensible, you can add these new index types fairly quickly.

And it was notable that when ChatGPT sort of became mainstream in like 2022-2023, and then RAG was the buzzword everyone was using, and they realized “oh, how do you do that? You need a vector index”—all the major database players added vector indexes within a year. A lot of them are leveraging open source libraries like DiskANN or FAISS from Meta. It wasn’t a big lift to go add these things.

Versus like when the column store stuff came around—that’s a pretty fundamental engineering change you have to make in your systems to support vectorized execution or column store stuff. Whereas with the vector indexes, you could plop one in and get it up and running fairly quickly.

[45:23] So to me, that shows that the moat for the vector database systems—the specialized systems—is not that wide. And certainly they’re going to do things a lot better than like pgvector for example, but for 99% of people, that’s probably good enough to use something like pgvector.

[45:46] Mike Stonebraker: Well, two other quick comments.

One is: fancy vector indexes basically are limited to main memory. So if you’ve got a problem that doesn’t fit in main memory, your performance is going to fall off a cliff.

And the second thing is: if there are a lot of updates to your vectors, it’s a hellacious problem to update the indexes. Just hellacious.

So to the extent that you have read-only small data, I think the vector indexes are just fine. But if you have a bunch of updates, then I think it becomes a much more complicated problem. And if you run the indexes in the same system of record as the data, then at least you can keep it consistent.

[46:54] Andy Pavlo: I mean, not super consistent, right? Because sometimes some of these indexes you got to rerun the clustering algorithm, and that means you got to rescan everything all over again. It’s the same challenge with the full-text search inverted indexes. They might have a sort of side buffer. You absorb all the writes and then eventually you got to run the more expensive rebuild job.

Part 6: GPU Databases and IBM’s Acquisitions#

[47:21] Host: Thanks. One other question about the market. Andy, you mentioned that Voltron shut down. There was a question about what that might say about the future of GPU-accelerated databases.

[47:33] Andy Pavlo: Okay, I gotta be careful here.

I have been skeptical about GPU databases for a long time. In 2018, we had a seminar series where we invited all the major GPU database vendors to come to campus. I just remember that they would tout all these amazing numbers, but they were only for databases that could fit in the memory of the GPU. And they would always beat up on Greenplum for some reason—like who cares about Greenplum in 2018?

So I was skeptical at the time because it seemed like a very niche thing—your data has to be small to fit in the GPU.

What had changed—and what Voltron showed in their thesis project or thesis system (although it didn’t have product-market fit or viability as a product)—they showed how to stream the data fast from disk into the GPU and have it treat the GPU as an accelerator to the overall data system without having to load everything in.

So to me, that’s the game changer. And without naming names, I would expect—you should expect to see some pretty big announcements in 2026 for major database vendors saying that they now support GPU acceleration.

[49:00] Host: Cool. And one more on the market. How is the acquisition of DataStax (Cassandra) and Confluent (Kafka and Flink) changing IBM’s position in the database market?

[49:07] Andy Pavlo: Oh, Mike was CEO of—or CTO of—Informix. He can tell you about IBM as well, right?

Look, I mean, DB2 still makes a lot of money. IMS is probably still milking the maintenance fees. They still make a ton of money on all these things. The IBM today is not the IBM of the IMS days, right? Certainly the culture and what they put out has changed.

So I think it remains to be seen, right? It remains to be seen whether how much they’re going to be deeply involved in the day-to-day operations of DataStax and Confluent—versus like a Red Hat style, you know, let them do their own thing almost as a satellite—or whether they’ll be quickly integrated and part of the overall consultancy stack of whatever IBM puts out there.

[49:56] Now, in the case of Cassandra, the number two contributor to Cassandra source code is actually Apple. Apple runs one of the largest—probably if not the largest—Cassandra clusters in the world that’s public. So I think Cassandra—the stewardship of Cassandra will be fine.

With Kafka, that remains to be seen. But again, Jay at Confluent is a smart dude. I’m sure they’ll figure something out.

[50:43] Mike Stonebraker: I think the thing you should all remember is that IBM is basically a services company and a custom software development organization.

What’s clearly happening is IBM customers have been asking for these two systems. So IBM has enough cash to just buy them.

But I think IBM has a legacy hardware business and a monumental legacy software business. And they are going to continue to milk that until everyone on this call is safely retired.

Part 7: The Future of Computer Science Education and Careers#

[51:33] Host: All right, let’s change topic a little bit and talk about computer science and how AI is impacting curriculums—you know, MIT, CMU, and elsewhere—and career opportunities.

In fact, somebody’s already asked on the Q&A box: what skills are required to get a job at a DBMS company? Maybe Andy, you can start by talking about how AI has impacted the curriculum at CMU.

[51:58] Andy Pavlo: Yeah, I would say right now nobody knows the answer, right? The LLMs are amazingly good at answering exam questions, homework problems, right?

Anecdotally, I would say in our intro database systems class, the first homework assignment is: we give you a dataset, we give you questions—kind of trying to solve the same problem Mike just talked about—and you have to write the SQL to answer the question. We’re fairly confident most of the students are using LLMs. And in fact, honestly, I say in the beginning of the semester we encourage them to use LLMs. It’s a tool that should be used by any developer now—like GDB or other debugging tools. It’s the way the world is.

But I will say though: at the end of the day, you have to understand the fundamentals. This is something where here at Carnegie Mellon, we’re placing a stronger emphasis on. We’ve always been very good at it, but now more than ever.

[52:55] It goes back to the vibe coding stuff. You can have LLMs generate a bunch of code, but if you don’t understand the fundamentals of what this code is trying to do or what you’re trying to achieve, then you’re going to be lost.

So I say the things you should be learning are the core fundamentals of computer science, and that part really hasn’t changed. It doesn’t matter if it’s in JavaScript, C++, Rust, or what—the language and the tooling may change, but the fundamentals matter. And being aware of what this software is trying to do for you.

[53:40] In terms of answering the question of what skills you would need to get a job at a database system company these days—again, I don’t think it has changed too much yet. Understanding system fundamentals, understanding a little bit what the hardware does.

The great thing about databases is you have to understand kind of everything—you touch everything. So you have to understand what the hardware wants to do, what the OS wants to do or not do for you, what the network wants to do for you. And understanding all these things.

And then I would emphasize the ability to interact and manipulate and understand large code bases that you didn’t write. Again, LLMs are helpful at these things.

[54:17] And also debugging—because that problem doesn’t go away. LLMs can’t solve that—I think they’ll eventually get there. But understanding how complex components fit together, interacting with each other to identify bugs, identify race conditions and other issues—that problem doesn’t go away. Those are the kind of things you just have to get through practice. And this can be done through a variety of ways.

I would say that the resources are significantly better than certainly when Mike was a student and certainly when I was a student. There are so many things now that can help people come to terms and understand what database systems are trying to do. It’s just a matter of doing it.

[54:59] Mike Stonebraker: I think as long as you come from a first-rate university, majoring in CS will be just fine—because it’s exactly what Andy said. You’ll be taught how to be productive utilizing all the tools that are available.

I think the market will be pretty terrible if you graduate from Control Data Institute or those kind of places—because then you’re just taught to code, and that’s not going to be a very marketable skill unless you’re super, super, super smart.

[55:48] So I think chances are the total enrollment in CS at major universities will be flat to down for a while. And after that, I have no idea what’s going to happen.

[56:00] Andy Pavlo: But I would say also too—on one hand, yes, it’s going to be harder to get jobs because AI helps a lot of things. But then going back to the vibe coding piece, it’s so much easier now to build stuff, right?

So the end goal shouldn’t necessarily be to go work at Google or Apple or whoever—you can just go do your own thing. And again, I realize that’s easier said than done for a lot of people given different financial situations. But that part is also exciting too—that the barrier to entry is significantly reduced.

But again, I would say you still need to understand the fundamentals.

Part 8: Q&A - Core Database Fundamentals#

[56:36] Host: There was a question related to the fundamentals. A few of them actually. People are asking: what do you think are the most important fundamental database internal concepts somebody should learn or master to improve their career opportunities?

[56:52] Andy Pavlo: I mean, one is—not to pitch my own thing—but we put all our course materials online on YouTube and you can do all the programming assignments, you can do all the homeworks, you don’t have to pay CMU any money. So it’s all there. By all means, dive in, go for it.

I mean, I would say it’s kind of the ACID piece, right? Atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability. Understanding what that looks like—how you move data from non-volatile storage into memory and interact with things. How do you make sure that people can access their data and not lose anything?

So those are sort of the high-level fundamentals. And as a part of that, you got to understand algorithmic complexity. You have to understand data structures. You have to understand optimization techniques. You have to understand concurrency control. A little bit of set theory for relational algebra stuff is always good too.

[57:54] I would call those the fundamentals. And then as I was saying before, the great thing about database systems is: whatever you’re interested in in the context of computing, you can do it in the context of databases.

If you like algorithms, there’s a lot of work in that space you can look at. If you like networking, you could do that. If you like programming languages, there’s a bunch of attempts to make SQL better or change SQL.

Whatever you’re interested in, you can do in the context of databases. And oftentimes people pay you a lot of money for it. So that’s why I’m pretty bullish about things.

Part 9: Why Did You Become a Database Researcher?#

[58:27] Host: Cool. We’re at the top of the hour, so one more question. This came from somebody in the registration form. The question was for each of you: Why did you choose to become a DBMS researcher?

Andy Pavlo: Mike, you tell the draft story.

[58:46] Mike Stonebraker: Well, the simple answer is: I went to graduate school only because I was subject to the draft way back then. And my choice was to go to Canada, go to jail, go to Vietnam, or go to graduate school. And that made things really simple.

Once I was in graduate school, I managed to stay there till I was 26, and the army didn’t want me anymore.

So then when I got a job—my thesis by the way I think is totally ridiculous—and when I got to Berkeley, I said, “Well, I have to have some way of getting tenure, and pick something, pick a new something to work on.”

[59:47] And the thing I found that made an astronomic difference was Berkeley gave me a mentor who was Gene Wong. And Gene said, “Let’s look at this—Ted Codd just wrote this pioneering paper.” This was in 1971; his paper appeared in CACM in 1970.

So we started looking at data stuff. Ted Codd’s stuff was easy, simple—you could understand it, it had some mathematical underpinning. The other proposal was from the Committee on Data Systems Languages (CODASYL), which was this low-level graph-structured thing that was a total mess.

And Gene and I looked at each other and said, “How can anything this complicated be the right thing to do?”

So that sort of set the path. A lot of it was happenstance, but a lot of it was getting a mentor when you land at whatever university you’re going to try and get tenure at.

[1:01:06] Andy Pavlo: Mike’s story is a bit more prolific.

In my case, I was arrested in high school and I didn’t want to go to prison. So I looked at the Federal Bureau of Prisons statistical information about what is the lowest population of Americans that are in prison? And it was people that had PhDs.

So I figured if I get a PhD, I’m less likely to go to jail or prison. So that’s why I decided to pursue that.

And then databases just sort of came naturally to me. I worked at a shady startup and we switched over to MySQL. I learned the relational model when I was in high school. It was awesome.

Mike Stonebraker: And you should talk about the time you actually did go to jail.

Andy Pavlo: Uh, well, hold on. When I was arrested, we pled guilty to local charges and didn’t go federal. So I never went to prison or jail.

But I did try to propose to my wife in prison. They never actually put me in jail, Mike, because they were concerned that once I get in jail, then I’m under their insurance. So if I got in trouble or got hurt, they would get fired. So I was outside in the holding area.

[1:02:25] Host: Um, okay. Not the answers I was expecting, but excellent.

Closing#

[1:02:31] Host: All right, so I think we’re going to have to wrap up now. I’m sorry we couldn’t get to every question.

Want to thank Mike and Andy, and Jen from DBOS for helping out with the webinar today and sharing your wisdom and experience.

Want to wish you guys and everybody online a great holiday season and happy new year, and look forward to seeing you on an event in 2026.

End of transcript.

Summary & Translator’s Commentary#

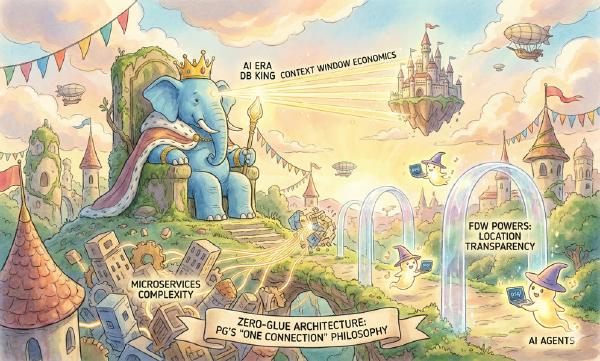

The following section contains the translator’s (Vonng’s) summary and commentary on the key points discussed in this conversation.

Mike Stonebraker’s Core Views#

1. Skeptical of LLMs for Text-to-SQL#

Summary: Testing LLMs on real enterprise data warehouses yields near-zero accuracy. Four key reasons: non-public data, idiosyncratic terminology, semantic overlap, and complex queries. Mike advocates wrapping data sources in SQL and letting query optimizers solve the problem rather than relying on LLMs.

Commentary: This is a sobering reality check on Text-to-SQL hype. Academia and media tout 60-90% accuracy, but that’s on toy datasets. In real enterprise environments—like MIT’s data warehouse where “Course 6.2” means “Computer Science”—LLMs immediately fall apart.

This reveals a fundamental limitation of LLMs: they’re pattern matchers, not reasoning engines. The “dark knowledge” of enterprise data—implicit business rules, legacy terminology—isn’t in the training corpus, so LLMs are helpless. Mike’s “SQL wrapper + query optimizer” approach essentially admits: structured problems still need structured solutions.

2. Agentic AI Needs ACID, Database Technology Will Shine#

Summary: Current agentic AI is “read-only”; it will soon become “read-write.” Once updates are involved (like online shopping flows), you need transaction semantics—atomicity, durability, rollback capability. This is exactly what database technology has solved for decades.

Commentary: This is Mike’s most prescient observation. Current AI Agent frameworks are essentially “optimistic execution”—assuming everything goes well, retry on failure. This is a disaster in real business scenarios.

Mike’s bicycle shop example is clear: check inventory → verify credit → collect payment → ship product. Each step can fail, and failure requires rolling back previous operations. This isn’t a new problem—this is exactly what ACID transactions solve, just wearing an AI costume.

I fully agree with this assessment: in the next 1-2 years, database technology (especially workflow transactions, Saga patterns) will become core infrastructure for Agentic AI. DBOS has positioned itself well here.

3. Postgres Has Won, Betting on Postgres is Correct#

Summary: All major cloud vendors have chosen the Postgres wire protocol. Postgres’s governance model is “open source as it should be”—community-owned, no single enterprise in control. Oracle’s acquisition of MySQL soured community trust; Postgres benefited.

Commentary: This is a statement of fact, not a prediction. Postgres has indeed won—at least in the open-source relational database space. AWS Aurora, Google AlloyDB, Azure Horizon DB, Supabase, Neon… everyone is playing in the Postgres ecosystem.

As the creator of Postgres, Mike saying this might seem self-serving, but objectively he’s not wrong. MySQL under Oracle has indeed declined—this year Oracle laid off almost the entire MySQL team.

One addition: Postgres won the “protocol war,” but this also means the PG distribution war is about to begin.

4. Vector Databases are “In-Memory Graph Indexes + Relational Blobs,” Narrow Moat#

Summary: Vector databases are essentially JSON blobs with graph-structured indexes. Two major limitations: only works in memory (performance cliff when data is large), updating indexes is a nightmare.

Commentary: This is the most precise takedown of vector databases. Pinecone, Weaviate, Milvus are hyped, but Mike’s one sentence bursts the bubble: you’re doing nothing more than what a Postgres extension can do.

Indeed—after pgvector emerged, most scenarios don’t need specialized vector databases. Mike says “99% of people can use pgvector,” and Andy agrees.

Vector database companies’ way out: either achieve extreme performance (serving that 1% of large-scale scenarios), or transform into complete databases (add transactions, add SQL)—but the latter means competing head-on with Postgres, essentially a dead end.

Andy Pavlo’s Core Views#

1. Vibe Coding is Real, LLMs are Changing Software Development#

Summary: Andrej Karpathy’s “vibe coding” concept is becoming reality. CMU’s course projects can now be almost entirely solved by LLMs. Code quality is about the same as human-written—because both learned from the same code corpus.

Commentary: Andy is 40 years younger than Mike; his optimism reflects the new generation of researchers’ mindset. Vibe coding is indeed happening—the proliferation of GitHub Copilot, Cursor, and Claude Code proves it.

But Andy has a key caveat often overlooked: vibe coding only works for greenfield projects. He himself admits 95% of enterprise programmers aren’t doing greenfield development. Those decades of accumulated legacy systems—repeatedly “updated, maintained, hacked”—LLMs are equally helpless with.

So vibe coding’s real impact may be: accelerated new application development, but legacy system maintenance remains a nightmare. This will exacerbate the polarization between new and old—more new systems written with AI, old systems increasingly untouchable.

2. Database Auto-Tuning Needs LLM + Specialized Algorithms Combined#

Summary: Specialized tuning algorithms are 2-3x better than LLMs, but LLMs are much faster (15 minutes vs 50 minutes). The future direction is using “reasoning agents” to orchestrate—sometimes calling LLMs, sometimes specialized algorithms.

Commentary: This is Andy’s post-mortem summary as OtterTune’s founder. He’s clear about why OtterTune failed: form factor problem—requiring user authorization to connect, passive observation rather than active intervention. The new approach solves this pain point through a proxy model.

The “LLM + specialized algorithm” combined approach is very pragmatic: LLMs excel at quickly giving “good enough” answers, specialized algorithms excel at fine-tuning, using reasoning agents to orchestrate both is entirely feasible in engineering.

However, I’ve always had a question: does database tuning really need to be this complex? Most Postgres performance issues can be identified by an experienced DBA in 10 minutes. With a distribution like Pigsty, important parameters are already automatically tuned to “good enough for production”—what’s the marginal gain of going from “good enough” to “optimal”?

3. Core of CS Education Unchanged: Understand Fundamentals#

Summary: LLMs can solve CMU’s assignments, but students still need to understand fundamentals—ACID, data structures, algorithmic complexity, concurrency control. Languages and tools will change, fundamentals don’t.

Commentary: An old truism, but worth repeating in the AI era. Andy is right: if you don’t understand what the code is doing, it doesn’t matter how much code the LLM generates.

Mike is more blunt: people from Control Data Institute (vocational training) will struggle, but those from top universities will be fine.

The implication: programming is bifurcating—top talent designs systems, AI writes code, elite experts multiply their effectiveness by tens of times, ordinary programmers are eliminated.

Brutal, but possibly the real future.

4. Vector Database Moat Isn’t Wide, pgvector is Enough for 99%#

Summary: Vector indexes are just indexes; Postgres added them within a year. Vector databases either specialize (secondary index) or add transactions/SQL to become complete databases—the latter means competing directly with Postgres.

Commentary: Andy completely agrees with Mike on this point—indicating this is the database community’s consensus.

Comparison of Views#

| Topic | Mike Stonebraker | Andy Pavlo |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward LLMs | Pessimistic, nearly useless in enterprise data scenarios | Optimistic, valuable in code generation and auto-tuning |

| Future direction | Database technology will dominate Agentic AI infrastructure | LLM + specialized algorithms, reasoning agent orchestration |

| Postgres | Has won, betting on it is correct | Agrees, but notes backend needs modernization (OrioleDB) |

| Vector databases | Narrow moat, essentially in-memory graph indexes | Agrees, 99% can use pgvector |

| CS education | Top universities fine, vocational training graduates will struggle | Fundamentals unchanged, but barrier to building things is lowered |

| Career motivation | Avoiding Vietnam War draft | Avoiding prison |

My Overall Assessment#

Mike Stonebraker represents “old-school wisdom”—50 years of database experience keeps him vigilant against technology hype. His skepticism isn’t from not understanding AI, but from having seen too many boom-bust cycles. His judgment that Agentic AI needs ACID databases is very precise—possibly the most valuable insight from this conversation.

Andy Pavlo is the “pragmatic new generation”—neither blindly optimistic nor clinging to old views. He acknowledges why OtterTune failed and adjusted strategy to OEM integration; he sees vibe coding’s real impact but admits it only works for greenfield projects. As an academic, he maintains a rare commercial sensibility.

The consensus between them is more important than their differences: Postgres has won, vector databases are overrated, fundamentals matter more than tools, AI won’t replace people who understand systems.